|

| Chet Helms, late 60s (also: some guy) |

From the very beginning, the Grateful Dead had always tried to become a self-contained organism. One of their goals was to have some sort of permanent venue, where they could rehearse and perform at will. In the earliest days, the band even strove to live in such a place, although they only achieved it briefly at Rancho Olompali in Marin in the early Summer of 1966. Even though the band members' expanded personal lives pushed against communal living, the band was still looking for a room of its own. In old 1967 interviews, you can read about a mythical "Deadpatch." In 1968 the Dead took over the Carousel. These ideas persisted, and after 1995 the plan was resuscitated with "Terrapin Station," a permanent installation in San Francisco proper.

In early 1970, however, it nearly happened. The Grateful Dead office nearly merged with Chet Helms and the Family Dog on The Great Highway. The Dead and the New Riders had played the beautiful old ballroom on 660 Great Highway (near 48th and Balboa) many times in 1969, and they always played well. Why not make it home? The Family Dog would have had a "House Band" that ensured some financial security, and Jerry Garcia, Owsley and the Grateful Dead could have the run of the place. If they had released Workingman's Dead and had been anchored at a home base, the arc of their career might have been different.

Dennis McNally wrote about it, but it mostly gets forgotten. The very weekend that manager Lenny Hart was moving the offices, the Grateful Dead were getting busted down on Bourbon Street. On top of that, while Lenny Hart was moving, he wasn't showing Chet Helms the books, and Helms realized that Lenny's management was bent. Helms called off the merger. Calling it off was a sad but shrewd decision, since Hart was stealing from the Dead and would have stolen from Helms. Helms was counting on the Dead's capital infusion, and all they had was debt.

The Grateful Dead/Family Dog merger never reached fruition. Nor could it have worked, really, given the financial realities. But let's consider it anyway, as a path not taken.

The Grateful Dead, 1970: State Of Play

The Grateful Dead had been underground rock legends since their inception. More people had probably heard of them, however, than actually heard them. Their first three albums had not been successful. Aoxomoxoa, their third album, had cost over $100,000 and gone way over budget, so even if record sales were adequate, they wouldn't see any money from it for some time. The double album Live/Dead, however, constructed in parallel, had been released in November of 1969. It got spectacular reviews, probably got some FM airplay at new stations around the country, and probably sold a little bit.

Grateful Dead manager Lenny Hart had renewed the Grateful Dead's contract with Warner Brothers in 1969. Their initial 4-album deal would have expired with Live/Dead, but Lenny had extended it. The band didn't even know they were up for renegotiation. Hart probably pocketed the advance, since after he was fired it was revealed that he had stolen over $150,000. Meanwhile, the Dead were touring hard, winning fans everywhere they went, but without any strategy. Hart took gigs for the band as they were offered, and the Dead's touring schedule was not efficient, so they probably wasted money traveling unnecessarily to make gigs.

Meanwhile, the ambitious Jerry Garcia had numerous other plans. He was learning pedal steel guitar, and backing songwriter John Dawson in the New Riders of The Purple Sage. There was also a nascent plan to have some sort of country "Revue," seemingly called Bobby Ace And The Cards Off The Bottom Of The Deck. An ensemble that included Garcia, Bob Weir, the New Riders, Peter Grant and possibly others would play honky-tonk music and perhaps some originals, broadly in the style of the Porter Wagoner Show, which Weir and Garcia regularly watched on syndicated television. There was a lot going on in Deadland, and I'm not even counting soundman Owsley Stanley's mad experiments and Alembic Engineering's newly modified electric instruments.

|

| In the end, the Family Dog benefit was moved from Winterland to the smaller Fillmore West |

Family Dog, 1970: Plans and Portents

In 1969, the Family Dog on The Great Highway had mostly featured San Francisco bands as weekend headliners, while also open many nights of the week for a variety of community and entertainment events. Economically, the Dog had been a dismal failure. Undercapitalized to start with, the organization also had to get out from under a $5000 IRS tax lien, a substantial sum in 1969. By year's end, the Dog told the San Francisco Examiner that they were $50,000 in debt. A benefit concert, held at the Fillmore West of all places, had helped to keep the Great Highway operation afloat. At the time Helms promised, albeit vaguely, to have a new plan for the next year that focused on larger weekend events. The New Year had opened with some modest bookings the first two weekends (January 2-3 and 9-10), and then the Family Dog was dormant until month's end.

All the evidence we have for the first part of 1970 points to an ambitious, sensible plan by the Family Dog on the Great Highway. Helms was never explicit about these plans, however, for reasons that will become clear. I have had to piece together the outlines of the Family Dog's new arrangement from external evidence and a few after-the-fact reminisces, some of them from anonymous sources on Comments Threads (@anoldsoundguy, always hoping you can weigh in). I am providing my best guess, always subject to modification, and I should add that even if I am largely correct, Chet Helms and the Family Dog may not have used the modern terminology with which I describe the approach. Nonetheless, here's what all the evidence points to for the Family Dog's planned road to stability, even if they never got very far.

|

| The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, ca. 1969 |

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The

Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock,

and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the

Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the

Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized

the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their

successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are

what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.

In June, 1969, Chet Helms had opened the new Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway in San Francisco. It was on rocky Ocean Beach at the edge of the city--indeed, the edge of North America--far from downtown, far from Marin and Berkeley, and not even that accessible to the Peninsula by freeway. The former Edgewater Ballroom, built 1926, was a wonderful little venue. The official capacity was under 1500, though no doubt more people were crammed in on occasion, and it was smaller than the old Fillmore. Bill Graham, meanwhile, had moved out of the old Fillmore into the larger, more freeway-friendly Fillmore West, and he still dominated the rock market. Helms had opened the Family Dog on The Great Highway on June 13, 1969, with a sold-out Jefferson Airplane show, but the going had been rocky for the balance of the year.

|

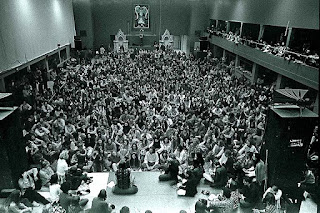

| One

of the only photos of the interior of the Family Dog on The Great

Highway (from a Stephen Gaskin "Monday Night Class" ca. October 1969) |

From January 30, 1970 onward, the Family Dog on The Great Highway only booked weekend shows, and the headliners were established bands with albums. It was a fact of San Francisco that just about all the headliners were Bay Area bands, as San Francisco was at the center of rock music at the time. So the Family Dog was in a unique position to feature largely local acts while still having headline bands with albums. In many cases, the albums were successful, too. So it wasn't exactly a "local" venue, but definitely home-grown. San Francisco is an insular place, so this was a potentially viable strategy. The Dog wasn't opposed to hiring touring bands, but they were more expensive, and in any case preferred the higher-profile Fillmore West.

Here and there the Family Dog

was used on weekdays for a few events, but it stopped trying to be a

community center. Weekend ticket prices were typically $3.50. That was

high, but not excessive. The shows were booked in order to make a profit

for the bands and the venue. The headliners in February and March read

like it was 1967 again: Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver, Steve Miller,

Big Brother, the Grateful Dead, Lee Michaels and Country Joe and The

Fish. All those bands were from the Avalon days, but they all had record

contracts and current or forthcoming albums, too. The first weekend booking was Jefferson Airplane, on January 30-31, 1970.

Step 2: New Finance

Clearly,

the Family Dog was recapitalized by the end of January. Although Chet

Helms had loyal support from the local bands that had played the Avalon,

they were all working bands as well. Helms could not have booked the

bands that he did from February through April without some cash on hand.

It is the source of the new finance that has never really been

explained, and that I have had to infer. Anyone who has insights or

knowledge into this area, please Comment or email me. I am noting in

advance that these are my most plausible guesses, and I am open to

substantial corrections.

As near as I can tell, Helms collected

contributions from local hippie entrepreneurs. My guess is that most of

them sold products that were--shall we say--not subject to taxation, nor

available in stores. Similarly, these same entrepreneurs did not want

their names publicly identified as a source of cash.

Step 3: A New Implied Business Model

Chet

Helms is often unfairly criticized as a poor businessman, because he

has always been compared with Bill Graham. Pretty much anyone wasn't as

good a businessman as Graham, certainly not in the rock and roll

business. Helms had his flaws as a business operator, but he was very

innovative, and in many ways I believe his approach to the Family Dog on

The Great Highway was innovative as well. For simplicity's sake, I will

use modern terminology to explain what appear to have been the outlines

of his plan. I'm sure that Helms himself would have used different

terms, but I'm not aware of a public or written statement.

The traditional criticism of Helms' business practices vis-a-vis Graham was that Bill charged everybody for tickets, and Chet let all of his friends in for free. By 1970, I do not believe that was the case. Based on Comment Threads, it appears that the Family Dog doorman had a Rolodex (address card file), and if your name was in that Rolodex, you got let in for free. Many of the names on that Rolodex were the hippie entrepreneurs that had laid out cash to keep the Dog going. In return, they got in for free whenever they wanted.

Was this a new model? Not really. It's how every museum in America was run, and largely still is. It's true that museums are not-for-profit and donations are tax-deductible, but Chet may have got to that over time. Certain people in the hippie community had money, and they contributed more of it in return for guaranteed admission. Today, the venerable Freight And Salvage club in Berkeley runs on this model. It's a very sound plan that could have worked.

Step 4: A High Profile Partnership

It

seems that Helms wasn't going to do this alone. He had a partnership

lined up, and his partners were going to be no less than the Grateful

Dead. The Dead were going to move their operation from Novato to the

Family Dog on The Great Highway. It some ways this may have been

designed as a replay of the Carousel Ballroom, but with an experienced

producer like Helms as part of the team. The New Riders of The Purple

Sage had played numerous dates at the Family Dog in 1969, so Jerry

Garcia clearly liked the place. Remember, there were only a few, tiny

rock clubs to play in the Bay Area at the time, so the 1000>1500

capacity Dog left room for the Riders to consider building their own

audience.

Of course, the Dead and the Family Dog did not

merge. The merger was scheduled for early February 1970, and that is

precisely when everything fell apart for the Grateful Dead. The band was

busted in New Orleans, putting the freedom of soundman Owsley Stanley

in great jeopardy, due to a prior LSD arrest. More critically, the Dead

discovered that manager Lenny Hart (drummer Mickey Hart's father) was an

outright crook, and had ripped the band off for $150,000, an enormous

sum at the time. The Grateful Dead were dead broke, without a manager

and without a soundman. Dennis McNally mentions the abandoned merger in his epic Dead history A Long Strange Trip, but it is remarked on almost in passing amidst

all the other tumult. McNally:

As the Dead had been busted in New Orleans [January 31], [Lenny Hart] had been in the process of moving their office from Novato to the Family Dog on the Great Highway, with Lenny to become manager of the FDGH as well as the Dead, and with Gail Turner to be the FDGH secretary as well as Lenny's. The idea of sharing space with the Dead appealed to Chet Helms, but became evident to him and Gail that the numbers weren't adding up and that there had to be at least two sets of books. Before anyone in the band even knew, Lenny moved the office back to Novato. [p.360-361].So just as Jefferson Airplane are re-opening the Family Dog, the Grateful Dead office is relocating to merge their businesses. Helms, while not Bill Graham, was neither a sucker nor a crook. Lenny Hart would have stolen from him, too, so he canceled the merger. The Grateful Dead themselves were probably unclear about what was happening, in between recording Workingman's Dead, worrying about Owsley and constantly performing. But the planned merger can't have been a secret in the local rock community. On Wednesday, February 25, Examiner columnist Jack Rosenbaum (the Ex's Herb Caen, if you will), had an item (posted above):

Love Generation: to help the Grateful Dead rock group build a defense fund for their pot-bust in New Orleans, Bill Graham staged a benefit Monday night [Feb 23] at Winterland, raising a tidy $15,000. So-0, the Grateful Dead have taken over the Family Dog rock-dance auditorium on the Great Highway--in competition with Graham.Rosenbaum was wired to local gossip, but not the freshest of rock news. Now, thanks to McNally (writing in 2003), we know that by late February the Dead-Dog deal was off. Still, the point here was that the word was around and had gotten to a city paper columnist, even if it was already a stale item.

1 1 |

| Kleiner Perkins HQ on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, a mile or so from the former site of Perry Lane |

A Brief Reflection

It's world-changing to imagine Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead with their own performance venue doubling as a rehearsal hall, on the beach in San Francisco. It's important to remember that it could not have happened. Lenny Hart had organized the deal, Helms had seen through the scam, and both entities were fairly broke. It's ironic that the local dealers probably loved the idea of supporting a partnership with the Dead, but could not publicly acknowledge themselves. The Dead/Dog merger could never have worked in the form in which it was conceived.

But let's take a moment to respect Helms for his forward thinking. The Edgewater Ballroom, which evolved into the Family Dog on The Great Highway, was torn down in 1973. But, just for a moment, let's say there was still an elegant 1500-capacity dance hall at Ocean Beach. What does the funding structure look like in 2022?

Proposition:- A Jam Band palace at Ocean Beach, on the edge of San Francisco

- The Great Highway converted to pedestrian only access (or nearly so)

- Cannabis entrepreneurs providing capital, and now able to publicly sponsor the hall

- For a membership fee, you would be guaranteed entrance without needing a ticket (within the confines of safety laws, of course)

- Participation and partnership from and with the Grateful Dead organization

Ocean Beach is near Interstate 280. You could head South and turn off at the Sand Hill Road exit into Menlo Park, where Kleiner Perkins and all the other Venture Capitalists started the tech boom. Kleiner Perkins helped found Amazon, Google and Twitter, among many other companies. You could arrange infinite financing on your iPhone before you even got to Sand Hill Road--before Crystal Springs, honestly--and just sign the deal when you got out of the car. Helms was just ahead of his time by 50 years or so.

It wasn't to be. Jefferson Airplane re-opened the Family Dog on Friday, January 30, but the plan was already crumbling around the Dog.

AppendixGrateful Dead and The New Riders of The Purple Sage at the Family Dog on The Great Highway

The Grateful Dead and the New Riders of The Purple Sage played many shows at the Family Dog. The band and particularly Garcia must have enjoyed playing there, or Lenny Hart wouldn't have made the proposition to merge the operations.

August 1, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Light Show Strike [Grateful Dead canceled] (Friday)

August 2-3, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/Albert Collins/Ballet Afro-Haiti (Saturday-Sunday)

August 12 or 13, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: New Lost City Ramblers/New Riders of The Purple Sage (Tuesday or Wednesday)

There is some uncertainty as to whether the Riders played on Tuesday (12th) or Wednesday (13th). Garcia and Nelson jammed with Mike Seeger and the New Lost City Ramblers for the encores. There was also an August 14 jam with the New Lost City Ramblers and Mickey Hart and The Hartbeats. It's not clear if that was a public event, or just a musicians jam.

For New Riders setlists during this period, see here.

September 7, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: jam (Sunday)

Garcia, Jorma Kaukonen, Jack Casady and others had some kind of jam on Sunday, September 7. It's unclear if other bands played.

September 11, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Purple Earthquake/Johnny Mars Blues Band/Wisdom Fingers/Osceola (Thursday)

There is a Grateful Dead tape fragment dated September 11. There is no other evidence that the Dead played the Family Dog, but it was "New Band Night" so maybe they showed up.

November 1-2, 1969, Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/Danny Cox/Golden Toad (Saturday-Sunday)

There was also a rehearsal/soundcheck on Tuesday, February 3.

February 27-March 1, 1970 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen (Friday-Sunday)

April

17-19, 1970 Family Dog On The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Mickey

Hart and The Hartbeats/Bobby Ace And The Cards Off The Bottom Of The

Deck/Charlie Musselwhite/New Riders Of The Purple Sage (Friday-Sunday)

I don't remember anything about this mysterious episode being written anywhere else besides the brief mention by McNally -- I hope some more documentation turns up someday.

ReplyDeleteI wonder how much the Dead were involved with Lenny's plan to merge with the Family Dog. You'd think after their Carousel experience, and being fully aware of the Family Dog's financial woes, they might be hesitant. But this being the Dead, maybe they thought it was a fantastic idea.

Of course Lenny had every reason to want to manage the Family Dog. No doubt he'd have driven it into bankruptcy in no time! "Sorry boys, we're just not selling enough tickets. How about another benefit show?"

We have only McNally to rely on for the timing, that Helms quickly whisked Lenny out of the Family Dog while the Dead were in New Orleans. It took the Dead another month to catch on, and it wasn't until the run of shows at the Family Dog at the end of February '70 when they finally held a meeting about it. "Early in March, Chet and Gail sat down with Ram Rod, McIntire, and Rock to talk things over." Ram Rod had had enough of Lenny, and March 2 was Lenny's last day as manager.