|

| The great guitarist T-Bone Walker, in his prime |

Matt Kelly had had a pretty good run as a musician in 1968. He had joined the embers of The New Delhi River Band, and along with bassist Dave Torbert and drummer Chris Herold, two members of the NDRB, that group had morphed into Shango. Shango played a few interesting gigs, and ultimately evolved into the group Horses. Horses was produced by the team of John Carter, Tim Gilbert and Dave Diamond, and they had already had produced some hits with "Acapulco Gold" by The Rainy Daze and "Incense And Peppermints" by the Strawberry Alarm Clock. Yet, despite a not-terrible album on White Whale Records, Horses went nowhere. The producers moved on to greener pastures, and Torbert, Herold and Matt Kelly retreated to the Bay Area to lick their wounds.

Both Torbert and Kelly took a hiatus from their professional music careers, albeit in different ways. Torbert took off for Maui at the end of 1968, and spent most of the next 16 months or so surfing. I'm not sure what else Torbert did in Maui--probably not much, since there wasn't that much to do--but as far as I know he was a true Surf Bum at a time when surfing in Maui was truly like surfing in paradise, as long as you weren't into civilization.

Herold, meanwhile, was a Conscientious Objector from the draft. He accepted alternative service, which in his case was driving a hospital truck. So from 1969 through 1971, Herold drove a hospital truck, and only played music on weekends. As a result, Herold played in a somewhat legendary but still part-time Santa Cruz Mountains band called Mountain Current. As far as I know, Mountain Current was a sort of prototype jam band, playing improvised, danceable music without a lot of structure. While never a major group, even in Santa Clara County, they would still turn out to play a significant part in the Kingfish saga, though not for a few more years.

Matt Kelly, meanwhile, was left without much to do in 1969. He had started being a professional musician around 1967, but by the end of 1968 he didn't even have a band. He'd played a fair amount of gigs around and about with the bands he'd been in, but he was just another harmonica player and rhythm guitarist on the Bay Area scene. Kelly loved the blues, but he was a suburban white boy who'd learned the music from records. However, although 1969 began inauspiciously for Kelly, the next few years would turn out to be pretty interesting. Kelly had an opportunity to really learn about the blues from the source, and then he made a record in England of all places. As a result, Kelly ended up playing a critical, though, unexpected role in the career of Dave Torbert and the history of the New Riders Of The Purple Sage.

The Blues

|

| Guitarist Mel Brown's I'd Rather Suck My Thumb album on Impulse! Records, recorded in Los Angeles in 1969 with Matt Kelly, and released in 1970. |

I'm not aware of Kelly working in any band in 1969, and I think he was just hanging out in the South Bay. As a result, one night in the Summer of 1969, Kelly and some friends went to a funky blues club in East Palo Alto called The Exit. At the club (and possibly on stage) was guitarist and singer Mel Brown. Brown wasn't a major figure on the white Fillmore circuit, but he was popular in the black West Coast blues scene. Kelly:

I was pretty mellow [but] I had a few drinks and my friends and I went to an all-black nightclub, an after hours club, where all the black musicians would go to play. We were the only white people in the club, we had a few drinks, and got a little loose, and quite to my own surprise I found myself walking towards the stage right in the middle of a song. I jumped right up and started playing along, which is not the kind of thing one does in a club like this; it was really kind of rough you could get yourself killed. In my case it worked to my advantage because Mel really liked my playing and saw potential in me. Mel basically said I’m doing a record in LA, I’m driving down the day after tomorrow, why don’t you come down with me? We did, we drove down in his Caddy. He lived in Watts, and in between sessions we would go to these blues clubs in LA and he would introduce me. He was a hero to the black community. I got to meet all these great blues players like T- Bone [Walker] and Jimmy Witherspoon. It ended up being a truly life changing experience for me. Aside from getting on Mel’s record that was how I made all my contacts with that world.Impulse! was mainly known as a jazz label, and its most prominent artist was John Coltrane. Nonetheless, the label released an album by Mel Brown.

I'd Rather Suck My Thumb-Mel Brown (Impulse 1970)

Mel Brown - guitar, vocalsMatt Kelly seems to have spent the Summer and Fall of 1969 getting a chance to hang out with Mel Brown and play with real blues musicians. Within two years, Kelly would end up forming a band that backed touring blues musicians, so Kelly plainly soaked up all the knowledge he could from Mel Brown about playing the blues and working as a blues musician. However, I have not been able to track down any actual performances by Kelly during this period, although I'm sure there must have been a few.

Matthew Kelly - harmonica

Clifford Coulter - organ, electric piano

Johnny Carswell - organ

Bob West - electric bass

Gregg Ferber - drums

Recorded July, August, October '69Rapp (RIP) -- vocals, bass, rhythm guitar (1971)

|

| Gospel Oak's sole album, released in 1970 on Kapp Records |

Kelly's few comments about his sojourn in England are very vague. This is not surprising, since it was some time ago, and no one save me is really concerned about the details. However, it seems that Kelly fell in with an American group called Gospel Oak. According to Kelly:

Actually what happened was I ended up going to England. I was playing in a band called Gospel Oak over there. The name came from a debunked underground station (tube station). I met up with these guys from Indiana who had a record deal with MCA Their manager was one of the publicists for the Beatles so it sounded like a really good deal.Just as musicians from all over went to San Francisco to emulate the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane, musicians went to London to emulate the Beatles.

Gospel Oak released an album on Kapp, an American MCA subsidiary. I have never heard the album, but supposedly it's OK. The band on the album was:

GOSPEL OAK (Kapp Records 1970)Gordon Huntley was not a member of the group. He was one of the very few pedal steel guitarists in England, and as a result played on many English recordings (Elton John's "Country Comfort" is probably the most well-known).

Bob LeGate-lead guitar, vocals

Matt Kelly-harmonica, guitar

Cliff Hall-keyboards

John Rapp-bass, vocals

Kerry Gaines-drums

plus Gordon Huntley-pedal steel guitar

I'm not aware of any performances by Gospel Oak in England. However, there must have been some record company support, so perhaps the band members got a weekly wage (a typical arrangement), and didn't need to gig. In any case, it seems that the record company must have been willing to pay to fly someone over, because it appears that Gospel Oak needed an extra member. This is how the otherwise obscure Yanks-In-England band played a part in the Grateful Dead saga. Kelly:

I wrote to Torbert, who was in Hawaii, and we sent him money for a plane ticket. He was going to fly over and join the band. From Hawaii, he stopped at his parents for two days to pick up a few things and fly to London from there. While he was there at his parents he got a phone call from David Nelson of the New Riders of the Purple Sage who said: 'we have this new band with Jerry Garcia on pedal steel and we would really like for you to play bass.’ David had a difficult time with this so he called me up and told me the situation and I said ‘yeah. Go for it. Do it.’Like many parts of the New Riders saga, this story has been repeated so many times by all the participants that it is universally accepted at face value. I myself have never entirely bought it. David Gans kindly took up my request to ask David Nelson about it, and Nelson conceded that it was no coincidence that Torbert got a call at his parents house on his way to England.

Think about this for a minute. David Nelson and Dave Torbert were in a band together for years, and John Dawson was a good friend of Torbert's as well. Torbert had been in Maui since late 1968, far from civilization, and he gets a surprise letter from Matt Kelly, followed by a plane ticket to London to join his band. Do you think that Nelson or Dawson just happened to be calling Torbert's parents in Redwood City on the day that Torbert dropped by (I have heard this version of the story)?

Garcia had been playing with Nelson and Dawson since May of 1969. By early 1970, as I have obsessively documented, the New Riders were on an enforced hiatus since they had no bass player. Phil Lesh had lost interest, and rehearsal bassist Robert Hunter was never actually invited to join the group. It seems obvious that Nelson and Dawson knew exactly when Torbert would be coming through town. So it's clear to me, at least, that they let Matt Kelly's record company send Torbert a ticket to get back to San Francisco--the 1970 Grateful Dead were effectively bankrupt--and then pitched Torbert the chance to join the New Riders.

Was Dave Torbert surprised to arrive at his parents' house in April 1970 and get offered the bassist's job in the New Riders Of The Purple Sage? Probably, he was surprised, but it wasn't a coincidence. Nelson and Dawson knew when he was coming, because clearly Torbert had told them. By pitching him over the phone, Torbert was legitimately able to present it as a surprise to Kelly. Kelly, to his credit, recognized what a good opportunity it was for his friend, and told Torbert to take the offer. Kelly:

This worked to my advantage later on because Gospel Oak ended up breaking up and when I came back from London, I started sitting in and playing with the New Riders. Out of that and some recording sessions that I had been working on, David quit New Riders and we started Kingfish together. That was in 1973.The close friendship between Kelly and Torbert was confirmed by Kelly's willingness to let Torbert try for the brass ring when he had the chance. So when Kelly and Torbert decided to form a band in 1974, Torbert knew he had a loyal partner. In any case, Kelly's UK work permit apparently expired at the end of 1970, and he would have had to return to the States anyway.

Mountain Current

Matt Kelly's musical activities in 1972 have to be assumed somewhat. I have determined that Kelly's reconnection with Bob Weir took place during the recording of an album by David Rea, produced by Weir, recorded in late 1972. Rea's Slewfoot album will be the next post in this series, but it's clear that Kelly was not really hooked up with the Dead/New Riders crowd until '72. Kelly was thanked on the back of the late '72 New Riders album Gypsy Cowboy, so he was part of that scene from then on. However, while I'm sure Kelly hung with Torbert a bit, he wasn't yet really part of the Riders crowd in 1971.

Back in the Bay Area, former New Delhi River Band, Shango and Horses drummer Chris Herold was coming to the end of his mandated service as a Conscientious Objector. From 1969 through 1971 Herold had driven a hospital truck, so he had only been able to play music on weekends. Herold's primary, and perhaps sole, musical endeavor was to play drums for a band called Mountain Current.

Mountain Current does have a sort of famous or infamous status in the Santa Cruz Mountains from back in the day. They appear to have been a sort of "jam band," in a 60s kind of way. They may have had a somewhat floating membership, too. I have read a few descriptions of their music, and apparently they played danceable, free floating jam music, probably in the Fillmore style of open-ended blues. I don't think Mountain Current played many songs per se, or only used them as jumping off points.

Herold was the drummer in Mountain Current from 1969 through 1971. In the middle of that time, of course, Dave Torbert returned to California and joined the New Riders Of The Purple Sage. By the end of 1970, Mickey Hart stepped down from the drum chair of the New Riders. Whether or not Hart had intended to be a permanent member--probably not--he was apparently becoming increasingly stressed out from having brought his father Lenny in as the Grateful Dead's manager, even if the band themselves forgave him. In December 1970, the New Riders signed up Spencer Dryden as their new drummer, as Spencer had left the Airplane nearly a year earlier. I have to think that Nelson and Torbert would have wanted Herold as a replacement for Mickey Hart in the New Riders, but with Herold's obligation that would have been impossible.

The only other member of Mountain Current that I know was a temporary one, legendary South Bay guitarist Billy Dean Andrus. Andrus was the frontman for the popular San Jose band Weird Herald, fondly remembered by all who saw them (and by those lucky enough to have heard anything from their unreleased album on Onyx). Andrus was some character, however, and at one point around 1970 he was fired from Weird Herald, who temporarily replaced him with old Garcia pal Peter Grant. Andrus played with Mountain Current for about six weeks. Andrus liked to jam, and the suggestion was that he just plugged in and roared with Mountain Current.

How legendary was Billy Dean Andrus? He died in November of 1970, apparently after a wild party, and it hit all his friends hard, particularly those who were musicians. Jorma Kaukonen, one of his closest friends, wrote "Ode To Billy Dean," and Hot Tuna not only started playing the song by the end of that month, they still play it to this day. In 1970, Hot Tuna had played alternate weekends at a club called the Chateau Liberte, and Andrus would often sit in and jam. Hot Tuna had alternated with Hot Tuna at The Chateau with a then-unknown band called The Doobie Brothers. Doobie Brothers' guitarist Pat Simmons also wrote a song for Billy Dean, called "Black Water" ("Oh black water/Keep on rollin''/Mississippi Moon, won't you keep on shining on me"), and it became a worldwide hit that everyone recognizes. Pat Simmons still plays that song, too.

Other than Andrus and Herold, I have not been able to determine any other members of Mountain Current. However, I feel confident that Kelly must have sat in with them at the very least. Mountain Current evolved into a group called Lonesome Janet, led by Kelly and Herold, so it stands to reason that Kelly at least hung out and jammed, not least because Kelly didn't have many other rock music outlets in the Bay Area.

[update: Matthew Kelly himself was kind enough to give me some detail about Mountain Current. The band had a sort of floating membership, but Kelly did indeed perform with them regularly in late 1970. Besides Herold on drums, regular members at that time were singer Sweet John Tomasi, from The New Delhi River Band, electric pianist Mick Ward, "Bob The Bass Player," who may have been Bob Dugan, and Andrus on guitar. Different players came and went, and Kelly regularly played harmonica with them.]

Matt Kelly On The Chitlin Circuit

Gospel Oak ground to a halt in mid-1970, and Matt Kelly was left in London with no gig. Up until recently, Kelly's musical history for the next few years has been very vague. Recently, however, Kelly had a remarkable interview with scholar and dj Jake Feinberg, and Kelly spooled out the rather remarkable story of his career between the end of Gospel Oak and his permanent relocation to the Bay Area in 1973.

When Gospel Oak broke up, Kelly hooked up with New Orleans blues singer Champion Jack Dupree, who had been based in Europe since 1960 for a number of years, who was based in England at the time. Kelly played a few shows with Dupree, and must have hit it off, because Dupree wanted Kelly to come tour Europe with him, but Kelly could not get a work permit. As a result, Kelly returned to California later in 1970.

However, once Kelly returned to California, rather than finding another rock band, Kelly pursued his connection to the blues. He capitalized on the time spent with Mel Brown in Watts, and started working with organist Johnny Carswell, backing traveling blues musicians on the so-called "Chitlin Circuit." The Chitlin Circuit referred to the string of venues in the East, Southeast and Midwest that were wiling to book African-American performers, and more generally to the string of venues that featured black R&B performers throughout the country. By the early 70s, many of the bigger performers on the old circuit, such as B.B. King, were playing white rock venues as well. The circuit definitely tended toward older theaters in traditionally black neighborhoods--The Fillmore Auditorium had been a major stop on the Chitlin Circuit before Bill Graham took it over in 1966--and until then it was still a world removed from the white rock industry.

Carswell, Kelly and their band backed various touring blues musicians, with and without Mel Brown. The most famous of those was guitarist Aaron Thibodeux "T-Bone" Walker. Even this blog does not have enough space for a tangent on T-Bone, but suffice to say he was a fundamental influence on B.B. King, Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix, just for starters, so calling him monumental is almost modest. Due to his age and declining health, Walker never really had a chance to play for white audiences in the late 60s, but with his health improving in the early 70s it seemed like he could come back. If he had, Kelly might have gotten some real recognition. Kelly recalled

I ended up playing with T-Bone later on, right up until he passed away, which was really unfortunate because we were just getting ready to go into the studio and do a record. There are some live tapes floating around of stuff I did with T-Bone but they got lost somewhere over the years. If there is a guy out there named Red and you’ve got those tapes…boy I would be forever in your debt!

Kelly has some amazing reminiscences in the Feinberg interview, recalling being backstage with B.B. King, who told him that he owed his whole career to T-Bone Walker, or hearing Bobby "Blue" Bland tell Kelly his life story while killing time, waiting for his band to show up. For a typical suburban musician who had initially learned the blues from records he enjoyed, this was a remarkable opportunity for Kelly to become a part of the music that meant so much to him.

In 1973, it seemed like T-Bone Walker was primed for a comeback, and Kelly was expecting to go record with him down in Los Angeles. Just before that, however, KPFA-fm helped sponsor a big concert at the Berkeley Community Theater in June (1973), which Kelly recalled being dubbed "Night Of The Guitar." Besides great jazz players like Herb Ellis, T-Bone Walker represented the blues along with Shuggie Otis. Kelly and Johnny Carswell had put together a top-flight band to back T-Bone.

By 1973, Kelly's group was called "33," and they also featured local singer Patti Cathcart. My guess is that 33 sometimes just backed players on Bay Area dates, and sometimes they probably went on tour, as well. I'm not sure who else was in the band. In the Feinberg interview, Kelly alluded to "a drummer from the Doobie Brothers" being in 33, but whether that was a then-current (Michael Hossack) or future (Keith Knudsen) Doobie is unclear. Different players must have been in the group at different times, and I think Chris Herold drummed on occasion. Herold's Alternative Service would have been over by 1972, so he would have been more available (other possible members might have been Tom Richards on guitar and Bob Dugan on bass, but I haven't confirmed them).

Kelly described how 33 had worked up a popular rhythm and blues set, and then the star of the show--whether T-Bone Walker or someone else--would come out and do their set. Cathcart, well-known today as half of the duo Tuck And Patti, was probably the main lead singer for 33's set, and provided vocal support for T-Bone or anyone else. On her website, she recalls "my band "33" became T-Bone Walker's backup band in the last years of his life."

|

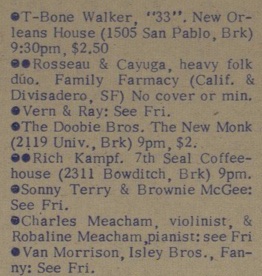

| Matt Kelly's "33" at the New Orleans House, February 3, 1971 |

Update; Esteemed scholar David Kramer-Smyth found a listing for 33 in the Berkeley Barb) February 3, 1971)

|

| Berkeley Barb "Scenedrome" listing for T-Bone Walker and "33" at Berkeley's New Orleans House (April 17, 1971) |

The Berkeley Barb listed "33" as supporting T-Bone Walker at the New Orleans House on April 17 and 18, 1971. T-Bone played a number of other gigs around the Bay Area at this time (including Palo Alto's Exit In, the Berkeley Blues Festival and possibly Chateau Liberte). Presumably 33 backed T-Bone on all those gigs.

Although the "Night Of The Guitar" was apparently a big success, according to Kelly the show was stolen by a young gunslinger named Robben Ford, soon to become quite well-known himself (see here for a picture of Ford with T-Bone and Shuggie Otis at Berkeley in '73). The tide was rising again for T-Bone, and Matt Kelly was looking to rise up with it. Tragically, however, T-Bone Walker became very ill and never performed after the middle of 1973. Walker actually lived a bit longer--I think he died in 1975--but he stopped performing, and Kelly was left with no recordings or even photos of his time on tour with one of the greatest electric guitarists of all time. Still, Kelly probably played with T-Bone the last time he did "Stormy Monday," and that's a great legacy by any standard.

|

| Matt Kelly was thanked by name on the back of the New Riders Of The Purple Sage album Gypsy Cowboy, released in December 1972 on Columbia, so he was definitely hanging with Dave Torbert by then |

According to Kelly, he had started to cut back on touring the Chitlin Circuit by 1973 in any case. The money would have been less, the theaters would have been more run down, and the old R&B circuit was shrinking. Obviously, a chance to participate in the triumphal return of T-Bone Walker would have been very special, but T-Bone's illness seems to have ended Kelly's run of playing with original bluesmen, for the most part. As a result, the second part of 1973 saw Kelly's return to the Bay Area rock music scene, which he had left back in 1968.

I assume Kelly must have looked up his old friend Dave Torbert when both were in town. Kelly is thanked by name on the back of the New Riders Of The Purple Sage album Gypsy Cowboy, released in December 1972, so we know that they were at least hanging out by the Fall of that year. Kelly would play on the next Riders album, Panama Red, recorded in the Spring of '73, so he was definitely working his way back into the rock scene. By the end of 1973, Kelly would be in another band, Slewfoot, and on the heels of that a band called Lonesome Janet, both of which would ultimately lead to Kingfish in 1974, but all that will have to wait for the next post.

_album_cover.jpg)