|

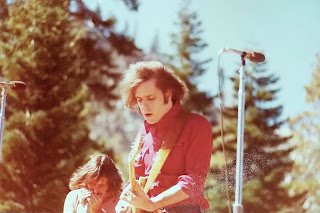

| Matthew Kelly and Bob Weir performing with Kingfish at Alpine Meadows in Lake Tahoe, CA on August 31, 1975 |

At the end of 1974, with the Grateful Dead on hiatus and apparently retired from performing, Bob Weir joined the local band Kingfish. A few fans who read the entertainment listings very carefully might have recognized the band's name, but otherwise they had been obscure up until Weir joined. Kingfish's only "known" member was bassist and singer Dave Torbert, who had left the New Riders of The Purple Sage at the end of 1973, after five albums. Weir would play full-time with Kingfish until the Grateful Dead returned to action in the Summer of 1976. He briefly played with them that Summer, too, but Kingfish kept going on throughout the 1980s. Weir, in fact, would periodically drop in and play with Kingfish, particularly from 1984 through '87. Although Torbert had passed away, Kingfish co-founder Matthew Kelly continued to lead the band throughout the 1980s.

I have already documented Weir's introduction to Kingfish in the Fall of 1974, all of his known performances in 1975 (so many that is has taken two posts, for Jan-June '75 and July-Dec '75) and a separate post for Kingfish up until Weir's departure in August '76. I have even documented Weir's assorted guest appearances with Kingfish from 1984 onwards.

This post will close the loop on

the last scaffold of the structure, the various Bay Area bands that led

to the formation of Kingfish. Weir went to see Kingfish at a moment in

his career and that of the band where they all needed each other, and it

led to a musical partnership that would thrive for a dozen years.

Summary: Kingfish Pre-History

Since Dave Torbert was a critical part of New Riders history, I have done extensive research on his 60s backstory, mainly with the New Delhi River Band. The New Delhi River Band, Palo Alto's other psychedelic blues band, with Torbert and Dave Nelson, was formed in the Summer of 1966, found its identity in the Fall, almost thrived in 1967 and finally faded by early 1968. Dave Torbert teamed up with Matt Kelly in a variety of 60s bands (Shango, Wind Wind and Horses), and finally moved to Hawaii. Kelly had his own complicated career, playing with blues musicians on the "Chitlin Circuit" while also playing in bands in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Kingfish had formed as a quartet in Palo Alto in Spring 1974. After a few local gigs, they had spent the entire Summer in Juneau, AK, playing lucrative gigs for oil workers. Kingfish returned to the Bay Area in October 1974. After October, the Grateful Dead had decided to stop performing live, and Bob Weir apparently missed the action. In any case, he had no source of day-to-day income. Weir was old friends with Matthew Kelly, and knew Torbert from the New Riders, so he attended a Kingfish show in San Mateo and offered to join the band. The surprised band members were delighted to have Weir's unique guitar playing, and the band immediately became a popular club attraction around the Bay.

Although Dead fans understandably associate Kingfish with Bob Weir, in fact the band had a history before him. Yet the origins of Kingfish have only been addressed in the vaguest of fashions, since Weir does not enter the story until the story is well along. I have looked into the musical history of Dave Torbert and Matt Kelly in great detail, thanks in particular to the contribution of Matthew Kelly himself.

I'm me, however, and my attention to microscopic historical details has somewhat obscured the arc of the founding of Kingfish, and how Bob Weir came to intersect with them. Matthew Kelly was kind enough to take the time to talk to me in February 2022--from Thailand, no less-- and unraveled some of the critical details of Kingfish’s history, so I can present a picture of the entire saga. This post will take a broader view of the background of the various ensembles of Kelly and Torbert from 1966 through 1973, showing how they all led to Bob Weir's 1974 integration into Kingfish. I will link to my prior posts for those who need to visit the rabbit holes themselves.

|

| Menlo School and College, 50 Valparaiso Ave, Atherton, CA, ca 2011 |

Bob Weir and Matthew Kelly both grew up in the well-to-do suburb of Atherton, just North of Palo Alto. Atherton is astonishingly rich today, but in the 1960s it was merely well-off. Kelly and Weir knew each other from a prep academy called Menlo School. Menlo School, also associated with a Junior College called Menlo College, had been designed as a boys feeder school for Stanford University (the girls were routed through Palo Alto's Castilleja School). Menlo School was founded in 1924, and is still active today (albeit co-ed and separate from the College). Kelly and Weir were both on the football team in 9th grade, which is how they became friends. Both had a nascent interest in music, but neither shared it with the other.

As to the other future members of Kingfish, Dave Torbert had grown up in Redwood City, the next town North of Atherton. His parents were both music teachers. Drummer Chris Herold grew up in Los Altos, two towns South of Atherton (with Palo Alto in between). Robbie Hoddinott was from Los Altos, too, although he was much younger than the others (Hoddinott was class of '70, and Weir would have been class of '65, had he graduated).

|

| The 1962 Menlo School Yearbook JV Football Team photo. Members of the team included Bob Weir (5th-L) and Matthew Kelly (4th-R) |

Weir would get kicked out of Menlo School. Weir, dyslexic and a charming troublemaker, would actually get tossed out of a number of prep schools, finally ending up in the nearby public Menlo-Atherton High School before dropping out to "join the circus," as he described the Grateful Dead. Kelly finished High School at another Prep School. He graduated (class of '65) and was a freshman at the University of Pacific in Stockton.

|

| Matthew Kelly's band played a gig at the tiny Fremont, CA psychedelic outpost The Yellow Brick Road |

First Blood, 1965-67: The Good News, St. Mathews Blues Band and The Grateful Dead

Bob Weir joined the Warlocks when they formed in the Spring of 1965, out of the ashes of Mother McRee's Uptown Jug Band Champions. New information indicates that their first show was at a Menlo School dance in April 1965. By year's end, the Warlocks had evolved into the Grateful Dead.

|

| Dave Torbert's band The Good News rocking out at Bob Weir's sister's Debutante Party at the SFO Airport Lounge on June 24, 1966 (note guitarist Tim Abbott's Day-Glo pants) |

Dave Torbert had played in a Redwood City folk group called The Sit-Ins when he was in High School, but I don't think he was a founding member. Torbert would go on to play guitar and sing in The Good News, Redwood City's first blues band. The Good News stood out because they wore "Day-Glo" clothes and brought a strobe light to their concerts, a precursor to the light shows that would become standard in the 60s. They were a popular local band, playing in the style of the Butterfield Blues Band. The Good News played Wendy Weir's debutante ball at the SFO Airport lounge on June 24, 1966 (brother Bob's band was otherwise engaged). I have discussed the history of the Good News at length. The band did play the Fillmore, but broke up soon afterwards. Both Torbert and drummer Chris Herold would join Palo Alto's New Delhi River Band.

Matthew Kelly had gone to the University of The Pacific in Stockton. He formed his own band, the St. Matthews Blues Band, and they played around Stockton and San Francisco. The St. Matthews Blues Band opened for Jefferson Airplane at UOP sometime during the 1965-66 academic year. Kelly dropped out of UOP, but the St. Matthews Blues Band played around throughout 1967. Sometime in 1967, Kelly picked up a hitchhiker in Palo Alto on his way to San Francisco. The hitcher, one Robert Hunter, asked to be dropped off at 710 Ashbury, and invited Kelly in. Kelly bumped into his old football chum Weir, so they both found out the other was a musician. Still, they would not cross paths again for another 5 years.

1968: Shango and Horses

The New Delhi River Band had featured David Nelson and Dave Torbert on guitar and bass, Herold on drums, and singer John Tomasi (along with lead guitarist Peter Schultzbach). The New Delhi River Band was popular in the Santa Cruz and Santa Clara County underground scene, but never found traction anywhere else (I have discussed their history in great detail). The NDRB finally ground to a halt around February 1968. Kelly's band had also folded, so he formed Shango with Torbert and Herold. Guitarists Tim Abbott and Ryan Brandenburg filled out the band. Brandenburg departed, and ultimately Shango used the name Wind Wind for a short while in late 1968.

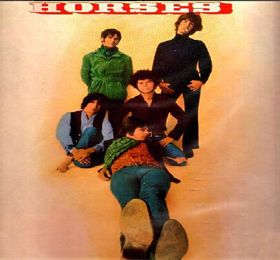

In between, however, Torbert, Kelly and Herold had reconfigured Shango as a band called Horses. Horses even released an album on White Whale Records, produced by the team of John Carter and Tim Gilbert. The pair had produced a surprise 1967 hit called "Acupulco Gold" with a Colorado band called the Rainy Daze. Carter had deep connections with Kelly from Menlo School. While Kelly had been a day student, since he lived nearby, Carter had been a boarder, where he had become friendly with another boarder, the former child actor Tim Hovey. Hovey and Kelly were very close, so Kelly knew Carter as well. Hovey was part of the Shango crew, writing songs with Torbert and probably acting as a roadie. Carter and Gilbert made some changes to Shango (adding future Sammy Hagar guitarist Scott Quigley [aka Scotty Quik] and singer Don Johnson (no, not that one). The forgettable album did include two songs that would become part of the Kingfish repertoire ("Asia Minor" and "Jump For Joy").

By mid-69, Wind Wind had ground to a halt. Kelly formed a somewhat casual group called Mountain Current (today we would call it a "Jam Band") with flexible membership. Chris Herold drummed when he could on weekends, otherwise performing alternative service (alternative to going to Vietnam) as an ambulance driver. Torbert wasn't doing much either, and he would move to Hawaii at the end Summer '69.

|

| Matthew Kelly played on Mel Brown's I'd Rather Suck My Thumb album. It was recorded in LA in Summer '69, and released on the jazz label Impulse in 1970. |

1969: Mel Brown

Matt Kelly's harmonica playing had been inspired by groups like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, who in turn had been directly influenced by Chicago blues musicians. Kelly knew the music, but he had learned about it from the outside--typical for most young white musicians at the time who had discovered the blues via records. Rather unexpectedly, this changed when Kelly went to an after hours club in East Palo Alto and impulsively jumped up on stage to blow some blues with the house band. Guitarist Mel Brown, well established in the African-American community, was in the audience. He chatted with Kelly afterwards, and invited him to come to LA and record (Kelly played on Brown's 1970 Impulse album I'd Rather Suck My Thumb). After spending time with Mel Brown in Watts, Kelly got hooked up with many of the established blues musicians on the (so-called) "Chitlin Circuit," and this would pay dividends for him in coming years.

|

| Gospel Oak's sole album, recorded in England, was released by Kapp Records in 1970 |

Fall 1969: England and Gospel Oak

There were a couple of centers of rock music in the Western World. One of them was London, home of the Beatles and Rolling Stones, and Kelly was one of many aspiring American musicians who wanted to make music there. In late '69, Kelly and his friend Tim Hovey drove across country on their way to London. Hovey was going to be involved in some kind of movie called "The Hashish Trail," about the hippies who went to the Far East in search of enlightenment, adventure and possible commerce. Hovey was a true world traveler, so he traveled on. But Kelly wanted to play music in London.

Kelly hooked up with a band from Indiana called Gospel Oak (Gospel Oak was a decommissioned tube station in North London). They had a deal with MCA, and recorded an album on Kapp Records (for more details, such as they are remembered, see my post here). The bass player left the group, however, so Kelly reached out to his old buddy Dave Torbert, sending him a plane ticket to go from Hawaii to London via San Francisco and join the band. As it happened, when Torbert dropped in at his parents house to get some (presumably warmer) clothes in April, he got a "coincidental" phone call from the New Riders, asking if he wanted to join a new band with Jerry Garcia. Torbert contacted Kelly, who told him to take the offer. Gospel Oak subsequently broke up. Kelly was going to tour the UK and Europe with Champion Jack Dupree, then based in Europe, but he couldn't get a work permit, so he returned to the Bay Area. Tim Hovey, meanwhile, was still following the "Hashish Trail," even though the promised movie was never made.

|

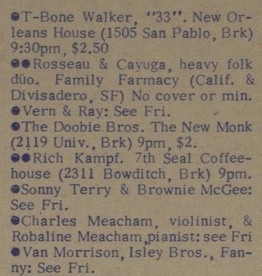

| Matthew Kelly and his 33 band backed T-Bone Walker at Berkeley's New Orleans House on Saturday, April 18, 1971 (from the Apr 17 Berkeley Barb--note the Doobie Brothers for $2) |

1970-71: Johnny Carswell and The Chitlin Circuit

Kelly returned to the Bay Area by the middle of 1970. He had several ongoing bands. He toured with organist Johnny Carswell, whom he had met through Mel Brown, playing authentic blues on the remnants of the Chitlin Circuit. The Chitlin Circuit booked shows in old theaters and venues that catered to African American audiences who liked blues and R&B. As a result, Kelly got to hear and meet many veteran (and legendary) blues performers, and got a chance to learn about the music he loved from the source.

In the Bay Area, Kelly put together the band "33", who backed visiting blues performers for their Northern California bookings. Although the membership of the band wasn't fixed, one of the regular performers was singer Patti Cathcart, who would later be better known as part of the duo Tuck & Patti. I think 33 would typically play an opening set at a club, and then be joined by the headliner. Kelly and 33 did some touring with guitarist T-Bone Walker, perhaps the greatest blues guitarist ever (certainly according to BB King).

Also during this period, Kelly continued to play with Mountain Current. Mostly they played at an infamous joint in the Santa Cruz Mountains called Chateau Liberte. The membership of Mountain Current continued to float, although it was built around former NDRB singer John Tomasi. On occasion it would include South Bay guitarist Billy Dean Andrus (from Weird Herald), or young Robbie Hoddinott, then still underage. Chris Herold drummed on occasion, Patti Cathcart would sometimes sing, and different players sat in as needed.

1972: New Orleans and The Soul Majestics

Kelly continued to tour around the country with Johnny Carswell, but finally it ground to a halt in early 1972. Kelly found himself in New Orleans. With no other options, he got a job on an oil rig, doing heavy labor under hot, difficult conditions. One day, one of his co-workers nearly lost his life until Kelly took a huge risk to save him. The grateful worker invited Kelly home to meet his family. The African-American family became good friends with him, and through them Kelly met and joined an R&B band called The Soul Majestics. Who knows? Matthew Kelly could have made final landfall in New Orleans, working in the oil industry and playing in an R&B band in a music capital.

But he didn't. Somehow, Kelly's old buddy Tim Hovey found out that Kelly was in New Orleans and came to visit him there. As you'll recall, Hovey had left Kelly in London in late '69, heading out to the Hashish Trail in Asia Minor. Hovey, a perpetual adventurer, had indeed gone on the fabled Hashish Trail, and even drove across Africa in 1971. In Spring 1972, Hovey followed the Grateful Dead across Europe, apparently catching the last three weeks of the Europe '72 tour. So Hovey hit New Orleans around June 1972, and Kelly decided to return to San Francisco with him. Kelly and Hovey had made it there by the Fall.

1973: David Rea and Slewfoot

With his return to the Bay Area, Kelly got re-integrated back into the music scene. Old buddy Dave Torbert was flying high with the New Riders of The Purple Sage, and Kelly played a little harmonica on their third album, Gypsy Cowboy, which was released in December of '72. Kelly also sat in with the New Riders for two songs on New Year's Eve ‘72 at Winterland. The Torbert connection paid a much more important dividend, however, since it ignited the career-spanning musical partnership between Kelly and Bob Weir. The two had been friends since junior high, of course, but they never played music together until early '73.

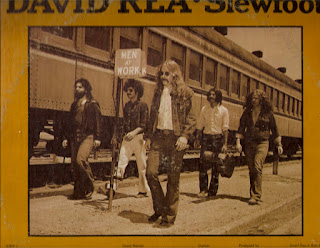

Columbia Records had signed Canadian guitarist David Rea, and somewhat peculiarly hired Bob Weir to produce his solo album in San Francisco. I have written about Rea's album Slewfoot, and what appears to be an odd only-in-the-70s story of how Weir came to produce the album. The sessions for the album were organized by New Riders guitarist Buddy Cage, not only a studio veteran himself but very likely an old Toronto pal of Rea's. Thus it is no surprise that most of the New Riders and their friends played sessions on the album (including Nelson, Torbert, drummer Spencer Dryden, Keith and Donna Godchaux, John Kahn and so on).

|

| Matt Kelly (2-r) on the back cover of David Rea's Slewfoot album |

In early '73, in anticipation of the album's release, Rea held auditions for his touring band. Kelly was invited to audition, no doubt through the Torbert connection. Weir--remember, he was the producer--re-connected with his old football pal. Sessions carried on for some time, and so Kelly and the other prospective band members actually played on Rea's Slewfooot album, released in Spring '73. When Rea started to tour around, he named his band Slewfoot. The band's lineup was

David Rea-guitar, vocals

Bill Cutler-lead guitar

Matt Kelly-harmonica, guitar

James Ackroyd-bass

Chris Herold-drums

Bill Cutler was a studio engineer and songwriter transplanted from New York City (his brother John would play a big role for the Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia in ensuing years). James Ackroyd had been the lead guitarist in the band James And The Good Brothers. He had remained in California when his partners (Bruce and Brian Good) had returned to Ontario. Old pal Chris Herold was on drums, another Torbert connection. Slewfoot played around the Bay Area for a few months, but David Rea was dropped by Columbia, probably because Clive Davis was pushed out of his position as President of Columbia Records.

Mid-1973: Lonesome JanetAfter July 1973, Kelly, Cutler and Herold seem to have left Slewfoot. Columbia had dropped Rea, but Slewfoot continued on as a trio (with Ackroyd on bass and Jay David on drums). In the meantime, Kelly formed a band called Lonesome Janet (don't google "Lonesome Janet" at work). Lonesome Janet mostly played the Santa Cruz Mountains, and seemed to have played a peculiar mixture of Top 40 and improvised jazz-rock. They played local hippie hangouts, and probably started out an evening playing familiar songs, while jamming them out longer and longer as the night wore on. Today we would probably call them a "Jam Band," but the term hadn't been invented. This formula was an extension of Kelly's band Mountain Current, from a few years earlier, but with a jazzier feel. The one song surviving from the Lonesome Janet repertoire is the Matt Kelly tune "Hypnotized," which was an instrumental in those days (Torbert added lyrics for Kingfish). Lonesome Janet's lineup was:

Patti Cathcart-vocals

Robbie Hoddinott-lead guitar

Matt Kelly-harmonica, guitar

Mick Woods-electric piano

Michael Lewis-bass

Chris Herold-drums

Pablo Green-percussion

Mick Woods was a black Englishman, as far as I know, and recalled by Kelly and Herold as an excellent musician. He would die in an auto accident in early 1974. Hoddinott (Mar 7 1954-Mar 6 2017) was only 19 when Lonesome Janet formed. I don't have any performance dates, but Chris Herold recalled playing a gay and lesbian bar in Santa Cruz called Mona's Gorilla Lounge when a biker fight broke out and the band had to hide in a walk-in freezer.

Lonesome Janet probably played most of the Santa Cruz County clubs at the time. Other Santa Cruz Mountains clubs at the time included The Catalyst (then still at the George Hotel on 833 Pacific Avenue), Mountain Charlie's in Los Gatos, the Chateau Liberte, the Town and Country in Ben Lomond, the Interlude (on Pacific Ave.), The Country Store, Original Sam’s, the Wooden Nickel, Andy Capp's, Chuck’s Cellar (in Los Gatos), The Crow’s Nest, the O.C. Inn, Margarita’s (now Moe’s Alley) and Dave’s Wintergarden. If any readers recall any specific Lonesome Janet gigs, please note them in the Comments.

Thanks to Rea and the Slewfoot sessions, however, Kelly had gotten into Bob Weir's orbit. In August 1973, the Grateful Dead were recording Wake Of The Flood at the Record Plant, and Kelly overdubbed a little harmonica on "Weather Report Suite." Kelly also sat in with the New Riders of The Purple Sage on occasion. In those days, the Riders shared management and a booking agency with the Dead, so they were very much part of the Dead scene.

Kelly also sat in at least twice with Jerry Garcia and Merl Saunders, once at the Great American Music Hall (on July 19, 1973) and another time at Berkeley Community Theater (October 2, 1973).

|

| Wing And A Prayer, Matt Kelly's 1985 Relix LP, based in part on his unfinished 1973 Harmonica Instruction album |

Late 1973: The Harmonica Instruction Album

In late 1973, while performing live with Lonesome Janet, Kelly embarked on the idea of recording a harmonica instruction album. The details are now kind of lost, but I think it was an album designed to illustrate different blues licks. I presume it would have had a companion instruction book, as well as standing on its own as a blues-styled album. Some of the material ultimately came out on Kelly's 1985 solo album on Relix Records, Wing And A Prayer.

In 1973, a lot of aspiring musicians wanted to play blues harmonica. Certainly, if you were the lead singer or rhythm guitarist in a band, and you could "blow some harp," popular songs like the Rolling Stones' "Midnight Rambler" or Canned Heat's "On The Road Again" could be added to your band's set. Yet while it wasn't hard to get a sound out of a harmonica, it was hard to play well, and there wasn't really anywhere to learn. So if there had been a good instruction book with some how-to examples on a record, it could have been a perpetual seller. Remember, music stores would have sold it, not just record stores--it could have been a unique opportunity.

Kelly found a budget somehow, and started recording some tracks. I think the idea was to demonstrate different styles and techniques, but Kelly never indicated what the plan was for the "instruction" piece. The material was released in 1985 by Relix Records as a Matthew Kelly album called Wing And A Prayer. As is typical with Relix albums, the credits are detailed but confusing (see the Appendix below). Some of the tracks were recorded in 1973 at the Record Plant in Sausalito, as part of the Instruction album, and other tracks were recorded in 1980. Overdubs seem to have been done throughout the 1980s. High profile guests on the album include guitarists Mel Brown, John Cippolina and Bob Weir, keyboardists Nicky Hopkins and Brent Mydland, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and many other names familiar to Bay Area music fans.

The Wing And A Prayer credits do indicate that the two tracks Jerry Garcia recorded were done in 1973. Mike Bloomfield was also recorded in '73, as was pianist Mick Woods (whose only known recorded appearance was on the two tracks on the Relix release). Chris Herold's drum parts were almost certainly recorded in 1973, but overdubs were done on every track for the next dozen years. Dave Torbert played bass on ten of the twelve tracks, but he surely recorded in both '73 and '80.

The "harmonica instruction" album was recorded in late 1973, when the New Riders were off the road after touring behind Panama Red. The Adventures of Panama Red was the Riders' fourth and most successful album (ultimately going Gold), and Torbert had written and sung many of the songs on the album. When Kelly told Torbert that he was planning to form a blues-oriented combo, he was very surprised to find out that Torbert wanted to join him.

Kelly told me that he actively tried to talk Torbert out of leaving the New Riders. Success can be fleeting in the music industry, and the New Riders had a big hit on their hands. The band had toured hard the previous few years, and had built up a good following in the Northeast and the Midwest. Torbert was willing to leave all that and throw in his lot with Kelly, who had really had no success as a recording artist. Now, sure, Kelly and Torbert were old pals, and Torbert's opportunity with the New Riders had only come because Kelly had graciously let him out of his agreement to join Gospel Oak, but Kelly still thought Torbert was foolish. Torbert was adamant, however. He was tired of the New Riders' country sound, and he wanted to play some bluesy rock and roll. So Kelly and Torbert started Kingfish.

|

| Tim Hovey's crash pad was near Palo Alto City Hall at 250 Hamilton Ave |

1974: Kingfish

Dave Torbert and Matthew Kelly started Kingfish in early 1974. Dave Torbert had given notice to the New Riders at the end of 1973, and the band knew that their concerts at Winterland on December 14-15, 1973 would be his last shows with the band. Torbert was replaced by ex-Byrds bassist Skip Battin, who was recommended by booking agent Ron Rainey. The initial lineup of Kingfish was

Robbie Hoddinott-lead guitar

Matthew Kelly-harmonica, guitar

Dave Torbert-bass, vocals

Chris Herold-drums

Mick Woods would have been a member of Kingfish--he may even have rehearsed with them--but he died in an auto accident in early 1974. Kingfish would spend the next year trying to find a fifth member to fill out the band. Old pal Tim Hovey had a "crash pad" in downtown Palo Alto, and Kingfish rehearsed in a the warehouse next door, near Hamilton Avenue. Hovey was Kingfish's soundman. Besides being Kelly's buddy from Menlo School, Hovey and Torbert had written songs for the Horses album in 1968. Herold, of course, went all the way back with Torbert to the Good News in Redwood City, and then the New Delhi River Band, Shango, Horses and Wind Wind. Hoddinott had played with Kelly and Herold in Mountain Current prior to playing with them in Lonesome Janet.

Old Peninsula hands will recognize the passage of time by the location of rehearsal hall downtown. Palo Alto had just built its new city hall 250 Hamilton Avenue, but Silicon Valley money hadn't yet really come into town. So there were still empty warehouses downtown, and cheap rentals in sprawling old Edwardian houses. The dynamics that had allowed Jerry Garcia and his pals to live hand-to-mouth downtown in the early 60s were still intact in the early 70s. Kingfish, however, was probably the last band to actually get started in Palo Alto outside of their parents' houses.

June 7, 1974 gym, Foothill College, Los Altos, CA: The Sons of Champlin/Kingfish (Friday) Benefit for KFJC-fmKingfish's concert debut was at Foothill College Gym in Los Altos on Friday, June 7, 1974, opening for the Sons Of Champlin. Foothill was the Junior College for the Palo Alto area. All the band members had played Foothill before in various prior bands. Ace researcher David Kramer-Smyth confirmed this with drummer Chris Herold.

Summer 1974: The Tides, Juneau, AK

Soon after their debut, Kingfish were booked in Alaska. This seemingly odd booking had to do with the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline (TAPS), which shipped oil from Prudhoe Bay, above the Arctic Circle, down to Valdez, near Anchorage. TAPS was constructed to reduce dependence on Middle Eastern oil. The unexpected result, however, was that numerous construction workers were making serious money in Northern Alaska, where they couldn't spend it. When they had time off in the Summer, they came to the warmer parts of Alaska with their pockets full and ready to party. As an added Summer bonus, daytime in places like Juneau lasted about 18 hours.

Kingfish were booked for two weeks at a club in Juneau, Alaska's capital city. They were a hit, however, and immediately received an offer to play the rest of the Summer, at a Juneau club called The Tides, in the Anchor Room. Kingfish played The Anchor Room for about six weeks. They played six sets a night, six days a week. They had some songs rehearsed, but they had to learn new ones as they went. According to Kelly, the band members would just ask each other if they knew a song (like a Beatles song), and if more than one knew it they would just start it up. After six weeks, Kingfish were a tight, swinging band.

We actually have a taste of the Kingfish sound from The Tides. In September, they tried out pianist Barry Flast, who had flown up from California. Flast recorded some tapes of his performances, our only record of the

pre-Weir Kingfish sound. Some of the later Kingfish material is in

place, but there are some interesting covers, too, like Dave Torbert

singing the Beatles "Get Back." The Flast tapes are dated September, 1974, so presumably that was near the end of Kingfish's residency in Juneau.

Flast (1950-2013) himself had an interesting history. While in college in Boston, he had formed the Tom Swift Electric Band with guitarist Billy Squier. The band became the "house band" at the Psychedelic Supermarket, opening for many of the famous bands who played the venue, including the Grateful Dead. Flast had ended up in San Francisco, and played in various groups. Flast had a lengthy music career in the Bay Area. Despite his failure to lock in a gig with Kingfish in 1974, he ended up in the band around 10 years later.

Kingfish returned to the Bay Area at the end of September. Kelly stayed on in Juneau another two weeks, backing a Nashville singer (whose name he has forgotten), but the band reconvened around October. Around this time, Kelly invited Bill Cutler to join Kingfish. Cutler was not as interested in focusing on the blues sound of Kingfish, however, so he passed and formed his own group, Heroes. Heroes included lead guitarist Scott Quigley (aka Scotty Quik) who had played in Horses, and who would later work with Sammy Hagar (the other Heroes were Austin DeLone, bassist Pat Campbell and drummer Carl Tassi).

Fall 1974: Enter Bob Weir

Kingfish started to play around the Bay Area in October of 1974. Kelly recalled having been booked at a lounge in San Mateo, on or near El Camino Real and the San Francisco Airport (he has forgotten the name of the lounge). Unexpectedly, Bob Weir came to see them perform. As all Deadheads know, after their October 20, 1974 performance at Winterland, the Grateful Dead had "retired" from live performances. This left band members with no opportunities to perform live, nor any real source of income. Only Jerry Garcia had already put together a regular ensemble to play local clubs. It appeared Weir had similar ideas. Weir suggested to Kelly that he join Kingfish.

Kelly and Kingfish were surprised, flattered and pleased. Weir and Kelly had played together on David Rea's Slewfoot album, notwithstanding their old friendship, so the relationship wasn't out of thin air. Torbert and Weir had shared a stage many times. Torbert, in fact, had played on Weir's Ace album, as well as "Box Of Rain." Of course, Weir was an even bigger "name" than Torbert and would attract immediate attention.

Kingfish had a Friday night booking at the legendary Boots And Saddle bar, at 8129 La Honda Road in La Honda. A general store had been founded in La Honda in 1868, and then a post office in 1873. There had been a bar, hotel and boarding house since 1877. It had changed owners, burned down or blown up (for insurance, apparently) over the decades. Of course it was a transit point for whiskey during Prohibition, as were most bars in the Santa Cruz Mountains in that era.

In 1945, the new owners re-named it Boots And Saddle. From the late 40s onward, there were Saturday afternoon jazz concerts. Boots And Saddle remained a weekend music bar into the 1980s. Mostly local bands played there. If you were lucky, nearby resident Neil Young might turn up, and maybe even bring his band, as he was as local as anybody. The bar finally burned down in 1984, under mysterious circumstances (it was at least the third time this had happened).

|

| Timbercreek recorded and released their own debut album, Hellbound Highway, in 1975, on Saddle Records. Formerly called Mose, they played original material in the style of Workingman's Dead. |

Local band Timbercreek had recently changed their name from Mose. Note that they are on equal footing with Kingfish, since more locals had probably heard of Timbercreek. Note also that Kingfish is not advertised as "featuring Dave Torbert of the New Riders."

Weir sat in with Kingfish, but apparently didn't sing any songs. Weir's unique style of guitar playing was more like a pianist than a rhythm guitarist, but that actually fit Kingfish's sound very well.

November 17 and 19, 1974 Lion's Share, San Anselmo, CA: Kingfish (Sunday and Tuesday)

There are tapes from both these shows. Weir sings a few songs. The Lion's Share, at 60 Red Hill Avenue in San Anselmo, just 10 minutes from downtown San Rafael, was the principal Marin County musician's hangout. The club usually wasn't open on Mondays, and Kingfish and Weir probably just invited themselves to play there on Sunday and Tuesday. Other bands probably played, too. Sunday was usually "jam night," and Tuesday was usually "audition night.

November 29, 1974 Chateau Liberte, Los Gatos, CA: Timbercreek/Kingfish (Friday)

The Chateau Liberte was going through a period of booking more established rock bands. The Kingfish booking there was the first time Bob Weir was advertised as a member of the band. The Chateau, a notorious and unique hideaway in the Santa Cruz Mountains, held about 200 people and mostly appealed to locals. Timbercreek had been a regular band there under the name Mose. We also have a Kingfish tape from the Chateau. Weir sang several songs.

|

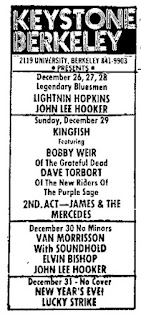

| The Dec 29 '74 Oakland Tribune ad for the Keystone Berkeley |

December 29, 1974 Keystone Berkeley, Berkeley, CA: Kingfish/James And The Mercedes (Sunday)

The Keystone Berkeley was the Bay Area's most prominent rock club. Jerry Garcia played there regularly. The Kingfish booking noting that Weir and Torbert were members of the band was advertised in the San Francisco Chronicle, Oakland Tribune and other major papers. To most Bay Area rock fans, the Keystone booking was the public notice that Weir had a new band.

James And The Mercedes featured guitarist James Ackroyd, from James And The Good Brothers, and included Frankie Weir, Bob's girlfriend, on backing vocals.

December 31, 1974 Stanford Music Hall, Palo Alto, CA: Kingfish/Osiris (Tuesday)

Kingfish played a New Year's Eve concert at a Movie Theater in Palo Alto, built in 1925 as the Stanford Theater, and then called The Stanford Music Hall. Mostly it booked stage musicals, but it had occasional concerts. The concert was promoted by an old Palo Alto friend named Paul Currier. Osiris was a Palo Alto band that included Kevin "Mickey" McKernan, Pigpen's younger brother, on organ and vocals. I have written about this concert at some length, so I needn't recap it all here. Suffice to say, from this point onwards Kingfish was booked regularly in nightclubs all over the Bay Area, and the Kingfish saga began in earnest.

Aftermath: Kingfish with Bob Weir, 1975-1987

Kingfish Performance History January-June 1975

Kingfish Performance History July-December 1975

Kingfish Performance History January-August 1976

Kingfish with Bob Weir, 1984-1987

Weir and Matt Kelly would remain partners in Kingfish until the band faded away in 1987--not counting an 1989 reunion. In between, Kelly and Weir worked together in Bobby And The Midnites and Ratdog, until Kelly moved to Hawaii. Nonetheless, they remained friends. In October 2022, Kelly joined Bob Weir and The Wolf Brothers for some of the Bob Weir 75th Birthday Celebration concerts at the Warfield Theater, extending the connection that had gone back to their junior high football team at Menlo School.

Appendix: Wing And A Prayer-Matt Kelly Relix Records RRLP 2010 released 1985 (CD release in 1987)

Five members of the Grateful Dead play on tracks on this album which is a collection of tracks recorded over a long period of time by a various groups of musicians. Bob Weir plays on three tracks, Jerry Garcia on two, Bill Kreutzmann on one, Brent Mydland on four and Keith Godchaux on one.

Tracks

Eyes Of The Night (Barry Flast)

Mona (Bo Diddley)

Dangerous Relations (Matt Kelly)

Over And Over (Matt Kelly)

Shining Dawn (Matt Kelly)

I Got To Be Me (Sammy Davis Jnr)

It Ain't Easy (Long John Baldry)

Riding High (Bill Cutler)

Next Time You See Me (Junior Parker / Sam Philips)

Mess Around (Armet Ertugun)

Harpoon Magic (Matt Kelly)

If That's The Way (Matt Kelly)

Musicians

The tracks on this album were recorded at different times with a wide range of musicians. The musicians on each of the tracks are as follows.

Eyes Of The Night;

Stan Coley - guitar

Barry Flast - vocals

Chris Herold - drums

Matt Kelly - guitar, vocals

Brent Mydland - vocals

Colby Pollard - bass

Rahni Rains - vocals

J.D. & Red - synthesizer

Bob Weir - guitar, vocals

Mona;

Patti Cathcart - vocals

John Cipollina - guitar

Robbie Hoddinot - guitar

Matt Kelly - guitar, percussion, vocals

Dave Torbert - bass, vocals

Dangerous Relations;

Ron Eglit - pedal steel

Jerry Garcia - guitar

Chris Herold - drums

Matt Kelly - guitar

Rahni Rains - vocals

Dave Torbert - bass

Bob Weir - guitar, vocals

Over and Over;

Sam Clayton - congas

Stan Coley - synthesizer

Robbie Hoddinot - guitar

Nicky Hopkins - piano

Matt Kelly - guitar

Brent Mydland - vocals

Mark Nielsen - drums

Dave Torbert - bass

Bob Wright - organ

Shining Down;

Fred Campbell - bass

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Stan Coley - synthesizer

Barry Flast - vocals

Robbie Hoddinot - guitar

Nicky Hopkins - piano

Matt Kelly - guitar, harmonica, vocals

Bill Kreutzmann - drums

Brent Mydland - vocals

I Got To Be Me;

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Dave Fogal - piano

Robbie Hoddinot - guitar

Matt Kelly - guitar, slide guitar

San Mateo Baptist Church Choir - vocals

Jerry Miller - guitar

Scotty Quick - guitar

Dave Torbert - bass

Bob Wright - organ

It Ain't Easy;

Michael Bloomfield - guitar

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Dave Fogal - piano

Matt Kelly - harmonica

Jerry Martini - horns

Jerry Miller - guitar

Scotty Quick - guitar

Rahni Rains - vocals

Dave Torbert - bass

Bob Wright - organ

Riding High;

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Bill Cutler - vocals

Ron Eglit - pedal steel

Jerry Garcia - guitar

Matt Kelly - guitar, harp, vocals

Rahni Rains - vocals

Dave Torbert - bass

Mick Ward - piano

Bob Weir - guitar, vocals

Bob Wright - organ

Next Time You See Me;

Mel Brown - guitar

Michael Bloomfield - guitar

Robbie Hoddinot - guitar

Matt Kelly - vocals

Jerry Martini - horns

Jerry Miller - guitar

Mark Naftalin - piano

Mike O'Neil - slide guitar

Dave Torbert - bass

Mess Around;

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Bobby Cochran - guitar

Chris Herold - drums

Matt Kelly - guitar, harmonica, vocals

Dave Torbert - bass, vocals

Mick Ward - piano

Harpoon Magic;

Buddy Cage - pedal steel

Patti Cathcart - vocals

Keith Godchaux - piano

Matt Kelly - harmonica

David Nelson - guitar

Rahni Rains - vocals

Dave Torbert - bass, vocals

If That's The Way;

Stan Coley - guitar

Nicky Hopkins - piano

Matt Kelly - guitar, harmonica, vocals

Brent Mydland - vocals

Dave Torbert - bass, vocals

Bob Wright - organ

Credits

Producer - Matt Kelly

Cover art - Karkruff/Canavan

Back cover design - Toni A. Brown

Layout - Brooklyn Bridge Publications

Part recorded at the Record Plant, Sausalito, 1973

Notes

- Many of the tracks on this release, including the two which include Garcia, were recorded in 1973. Further tracks were recorded in 1980.

- "Riding High" is titled as such on the track list of the CD but is called "Ridin' High" in the liner notes.