|

| Ralph Gleason's Chronicle column from Monday August 25, 1969 |

August 26, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: The Great SF Light Show Jam (Tuesday)

The paragraph from Ralph J. Gleason's column in the August 25, 1969 San Francisco Chronicle (above) says

Tomorrow night at the Family Dog on The Great Highway there will be a lightshow spectacular--The Great SF Light Show Jam--with 13 different light shows and taped music from three years of unissued tapes from the Matrix including tapes of Big Brother, Steve Miller, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service.

At the beginning of August 1969, many of the Light Shows in the Bay Area rock fraternity had joined together as the "Light Artists Guild" and tried to strike rock venues by picketing and withholding their services. The sole real attempt was Friday, August 1 at the Family Dog, for a Grateful Dead concert. Jerry Garcia purposely showed up late, the Dead did not play, and the "Guild" folded. Bill Graham, meanwhile, had simply laughed them off, threatening to do without light shows. Graham was ultimately correct, as Light Shows were no longer an important part of the attraction of rock concerts.

Light Show operators saw themselves as Artists, however,

and fairly enough. This Tuesday night show at the Family Dog attempted

to make Light Shows an attraction in themselves. Bill Ham had tried this

at a San Francisco place called The Audium, but that hadn't really worked.

The Family Dog effort would fail, too, after one more try in September. I don't

actually know of an eyewitness to either event. This blog has a

different interest, however.

I

had seen the Great SF Light Show Jam listed on various obscure flyers

and thought little about it, since Light Shows are inherently of the

moment. The idea that the Light Shows were performing to years of

unissued live shows recorded at the Matrix--well, that's something else

entirely. In the previous week's Berkeley Tribe, in an article about The Common and the Family Dog, there was some explanation:

Next Tuesday night Howard Wolfe [sic] will be playing tapes of some of the classic San Francisco rock concerts of the past few years. Wolfe, who worked with the Family Dog for two and a half years, wants to get together a musical and pictorial history of what went down in San Francisco. Nobody is better qualified to do it, he feels, than the people who created it in the first place.

Howard Wolf, based mostly in Los Angeles, had been the Avalon's booking agent in the 60s, as well as the booking agent for the Kaleidoscope. Wolf still had some involvement with the Family Dog on the Great Highway, although I'm not sure exactly what. However, with a little sleuthing, I'm pretty confident I've figured out what tapes Wolf was playing. For Deadheads, it's pretty interesting, with the caveat that the tapes were likely destroyed later and have never been heard since.

|

| The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, ca. 1969 |

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The

Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock,

and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the

Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the

Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized

the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their

successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and

after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted

memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through

December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are

what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.

In the Summer of 1969, however, with San Francisco as one of the fulcrums of the rock music explosion, Chet Helms opened another venue. The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, on the Western edge of San Francisco, was only open for 14 months and was not a success.

|

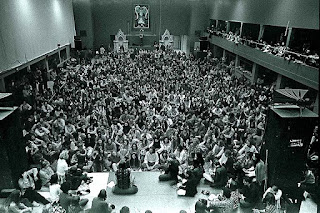

| One

of the only photos of the interior of the Family Dog on The Great

Highway (from a Stephen Gaskin "Monday Night Class" ca. October 1969) |

The Family Dog On The Great Highway

The Great Highway was a four-lane road that ran along the Western edge of San Francisco, right next to Ocean Beach. Downtown San Francisco faced the Bay, but beyond Golden Gate Park was the Pacific Ocean. The aptly named Ocean Beach is dramatic and beautiful, but it is mostly windy and foggy. Much of the West Coast of San Francisco is not even a beach, but rocky cliffs. There are no roads in San Francisco anywhere West of the Great Highway, so "660 Great Highway" was ample for directions (for reference, it is near the intersection of Balboa Street and 48th Avenue). The tag-line "Edge Of The Western World" was not an exaggeration, at least in North American terms.

The Family Dog on The Great Highway was smaller than the Bill Graham's old Fillmore Auditorium. It could hold up to 1500, but the official capacity was probably closer to 1000. Unlike the comparatively centrally located Fillmore West, the FDGH was far from downtown, far from the Peninsula suburbs, and not particularly easy to get to from the freeway. For East Bay or Marin residents, the Great Highway was a formidable trip. The little ballroom was very appealing, but if you didn't live way out in the Avenues, you had to drive. As a result, FDGH didn't get a huge number of casual drop-ins, and that didn't help its fortunes. Most of the locals referred to the venue as "Playland."

Old Deadheads are familiar with Vintage Dead, a 1970 Grateful Dead album on MGM/Sunflower. The album featured Dead tapes recorded at the Avalon Ballroom in 1966, with a vintage Avalon poster (from September 16-17, 1966) on the cover. Vintage Dead was raw, but back in the pre-cassette days it was literally the only window into the lost Grateful Dead world prior to the first album, the only hint of what the original Grateful Dead sounded like. But how had early Dead ended up on MGM Records 4 years later? Ben Fong-Torres explained the story in the October 28, 1971 Rolling Stone (reproduced at the wonderful Deadsources site):

NOT-SO-GOOD OLD DEAD RECORDS

SAN FRANCISCO - All Bob Cohen knows is that he didn't mean for it to happen, and he wishes the Grateful Dead wouldn't give him such weird looks whenever he's around them.Cohen is a sound man, and he was half-owner, with Chet Helms, of the Family Dog, back in the days of the Avalon Ballroom. As such, Cohen made, saved, and owns a pile of tapes of most of the bands that played there - the Grateful Dead among them.

And when Cohen was approached, in spring of 1969, by a Los Angeles record company to sell some of his tapes for an anthology of circa-hippie San Francisco bands, he could see no problem. It was Howard Wolf doing the talking, and Wolf's immediate past included the two Great Society albums Columbia had issued. And he was representing Together Records, a frisky new label headed by Gary Usher, former producer of the Byrds and Firesign Theatre, among others. In fact, the Dead saw no problems either when they were asked to sign releases for nine cuts. "We didn't dig the tapes, the quality that much," said Rock Scully, "but we thought it'd be nice to have this anthology of all the bands." With the Dead set, all Together had to do was get releases from enough of the other groups, like Big Brother, Moby Grape, Steve Miller, Quicksilver, Great Society, and Daily Flash. The idea was a three-LP package.

But, Cohen said, "they had trouble getting those releases." Then, "all of a sudden I find out that in one day Together ceased to exist! To settle everything, Gary Usher should have told me to get my tapes; I assumed the deal was off. My tapes are sitting there. But when I try to get them, I can't. MGM bought them."

A year later, out of the blue, there's an album on the market, Vintage Dead, on another new label, Sunflower (with MGM Records taking manufacturing and distributing credits) - not an anthology but, rather, a Dead album featuring five cuts, all Cohen's, along with, strangely enough, liner notes signed by Cohen. The Dead are wondering.

Then, three months ago, another album, Historic Dead, four cuts, two credited to Cohen, two to Peter Abram, owner and tape machine-operator at the old Matrix club. It is absolute bottom of the bag, the four songs totalling 29 minutes. Warner Bros., trying to sell contemporary Dead, are pissed. ("The Dead were freaked out because of the timing," Cohen said.

Vintage was released in fall of 1970, just after Warners had put out Workingman's Dead. Vintage Dead has sold more than 74,000 according to the latest word from Rick Sidoti, general manager of Sunflower Records.) The Dead, not knowing what's happening and not wanting to sound like they're being milked by the phone company, are pissed. And Cohen is suffering from this persecution complex, spinning around dizzily, wondering where to point his finger [for the complete article, see below or follow this link].

With the Berkeley Tribe's

mention of Howard Wolf, and the timing described here, it seems plain

that the live concerts from the Avalon and the Matrix were the ones

intended for Wolf's 3-album anthology. Fellow scholar runonguinmess tracked down Jerry Garcia's comment on the origins of the Vintage Dead material.

Jerry is asked about the Sunflower LPs in a KSAN interview from 1972-06-13 and comes up with a different angle. He says it was originally intended to be a fundraiser for the Family Dog on the Great Highway / The Common. Here's a transcript from fanzine "Hot Angel" No 9.

KSAN: What did you think - I don't want to get into areas of controversy but - what did you think of the live Dead? A couple of albums that were done for MGM - one I think and maybe another one in the works or something?

Jerry: There's the Historic and the Vintage.

KSAN: Bob Cohen asked for your permission I recall.

Jerry: Yeah well, see the thing was it was originally gonna be a whole different thing. It was originally gonna be - this was back in the days when there was a sort of a - an attempt to sort of communityise the Family Dog. It was after the - in the wake of that whole light show strike and all that stuff that was going on, and originally that record was gonna be made - the proceeds were gonna go toward keeping the Family Dog running at the time, and it was originally a whole different record company. But that - the record company that was originally doing it was bought up by MGM, there was some weird swindle went down and actually, as far as the music goes, well it's what we were doing in 66 and we weren't as good then of course as we are now, and - you know, but it is what it is.

Both of these sagas make sense--a record company mining historic material, for which there was a genuine market, while the Family Dog would have been one of the beneficiaries. Since the material had all been recorded back in 1966, none of the bands would have signed contracts yet, so the music was available for licensing. Using the tapes to finance the new Family Dog venue was a very hippie San Francisco concept, and one that was clearly not to be.

In the saga, the Dead are quick to give their consent, but no one else does. It's hardly surprising in retrospect. By Summer '69, Moby Grape was in litigation with their manager Matthew Katz--litigation that would go on throughout the balance of the 20th century--so no approval was likely there. Janis Joplin had a high-powered manager, Albert Grossman, who managed Bob Dylan among many others, and he wasn't going to be giving away historic product to support some hippie ballroom. Quicksilver Messenger Service and the Steve Miller Band had ambitious management, too, and they weren't going to cheerily sign away any rights any quicker than Albert Grossman. So the enterprise was never going to reach fruition.

It seems pretty clear, though, that 1966 music from the Avalon and the Matrix, recorded by the Dead, Big Brother, Steve Miller, Quicksilver, Moby Grape, Daily Flash and Great Society was blasted out over the Family Dog sound system, while the Light Shows did their thing on a Tuesday night. For those few who went, it would have been a genuine flashback to a recent era that was already long gone.

|

| Historic Dead, released on Sunflower/MGM in 1971, and recorded at the Avalon and the Matrix in 1966 |

Which Dead Tapes?

All Deadheads always have the same questions: which tapes were they, and where are the reels? Vintage Dead and Historic Dead had a total of 9 tracks, if only about sixty minutes of music. The five tracks on Vintage Dead were recorded by Bob Cohen at the Avalon. Because the cover of the album is the poster from September 16-17, it has generally been presumed that represented the show on the record. Scholar LightIntoAshes looked into the subject in detail, however, and determined that the most likely date was December 23 and/or 24, 1966 (not least because Weir sings "Winter's here and the time is right/ For dancing in the streets"). Historic Dead, much more poorly recorded, seems to be a mix of material from the Matrix (Nov 29 '66) and the Avalon. The Avalon date can't really be determined.

But what of the source tapes? Deadheads should brace themselves: Fong-Torres continues his story. Bob Cohen had discovered the tapes were sold to MGM, and tried to wreck the project:

[Cohen made] one desperate attempt at sabotage. He had given Together a set of mix masters, keeping the original tapes himself. "I went to their studios," ostensibly to identify tapes for MGM. "I looked at each box, and I had a big magnet with me and erased the tapes." To no avail. "They had quarter-track dubs made, too, and they were going to release those." Still, he contributed the liner notes for the Vintage album. He said he refused to do anything on the second one, which carries no information on recording dates or places.So Bob Cohen went and destroyed the tapes, but MGM had made safety copies and they released those. So there were some vintage Avalon tapes from 1966 played at the Family Dog in 1969, never heard before in the outside world. Some were probably played again in September (when a similar show was held on September 25). And then the tapes were destroyed, with only some dubs remaining, released on Vintage and Historic Dead. What else did the Grateful Dead play on December 23 and 24 1966? We won't ever hear.

You

can hold out hope, if you want, that Cohen kept his own copies of the

Grateful Dead tapes, as he implies that he had. But they have never

turned up in the Grateful Dead Vault or anywhere else, and Cohen himself says he has no Grateful Dead tapes in his

basement, although he has lots of other stuff. So 1966 Dead tapes, from

the Avalon, were played at the Family Dog in 1969, never to be heard

again. Sic transit gloria psychedelia.

Appendix: Vintage Dead article in Rolling Stone (complete transcript)

NOT-SO-GOOD OLD DEAD RECORDS-Ben Fong Torres, Rolling Stone, October 28, 1971SAN FRANCISCO - All Bob Cohen knows is that he didn't mean for it to happen, and he wishes the Grateful Dead wouldn't give him such weird looks whenever he's around them.

Cohen is a sound man, and he was half-owner, with Chet Helms, of the

Family Dog, back in the days of the Avalon Ballroom. As such, Cohen

made, saved, and owns a pile of tapes of most of the bands that played

there - the Grateful Dead among them.

And when Cohen was approached, in spring of 1969, by a Los Angeles record company to sell some of his tapes for an anthology of circa-hippie San Francisco bands, he could see no problem. It was Howard Wolf doing the talking, and Wolf's immediate past included the two Great Society albums Columbia had issued. And he was representing Together Records, a frisky new label headed by Gary Usher, former producer of the Byrds and Firesign Theatre, among others. In fact, the Dead saw no problems either when they were asked to sign releases for nine cuts. "We didn't dig the tapes, the quality that much," said Rock Scully, "but we thought it'd be nice to have this anthology of all the bands." With the Dead set, all Together had to do was get releases from enough of the other groups, like Big Brother, Moby Grape, Steve Miller, Quicksilver, Great Society, and Daily Flash. The idea was a three-LP package.

But, Cohen said, "they had trouble getting those releases." Then, "all

of a sudden I find out that in one day Together ceased to exist! To

settle everything, Gary Usher should have told me to get my tapes; I

assumed the deal was off. My tapes are sitting there. But when I try to

get them, I can't. MGM bought them."

A year later, out of the blue, there's an album on the market, Vintage

Dead, on another new label, Sunflower (with MGM Records taking

manufacturing and distributing credits) - not an anthology but, rather, a

Dead album featuring five cuts, all Cohen's, along with, strangely

enough, liner notes signed by Cohen. The Dead are wondering.

Actually, the Dead are more upset with Sunflower/MGM than with Cohen.

"We feel they've perpetuated a hoax on us," said Scully, once a manager

of the band. "At the very least, it was a misrepresentation." The Dead

just recently got hold of copies of the contract, the original having

vanished with Lenny Hart, the ex-manager they recently filed

embezzlement charges against. Hart was the Dead representative in the

deal, Scully said. "We found that those masters they said we'd signed

for had all been penciled in," he said. "Everybody who signed swears

there were three masters in there now that weren't in there before." But

the fact is, they signed, and there's little, legally, that they can

do.

Sunflower Records actually paid royalties to the band, $3650.51 in April

for 51,683 albums sold between September 1st, 1970, and February 8th,

1971.

Another statement to Cohen, citing identical sales figures, didn't

include a check, instead claiming that a $5000 advance cancelled out any

money owed. Which got Cohen further upset. "I haven't got any money

from them," he claimed, and when he wrote to Sunflower about it, "they

called me up and said they're putting out another album. Now they've

told me they're going to take both of them and put them together as a

two-LP package for Christmas!"

So Cohen was thinking about legal action. His friend and attorney,

Creighton Churchill, exchanged letters with Sunflower, and he learned

that the advance promised to Cohen was contingent on releases being

secured from all the bands on the 37 cuts Cohen had provided, and that

Sunflower, in the middle of the Together-to-MGM transaction, thought a

payment had been made. "So he can get the royalties," Churchill said,

"if he's lucky." Churchill also said that Cohen had in fact been paid a

separate fee of $1500 for giving the tapes to Together.

Cohen himself says Howard Wolf got the most money - "about $10,000 in

fees and expenses." But Cohen did more than his share of work. After

learning about Sunflower's plans for the Dead cuts, he said, "I talked

them into at least making it groovy. I put together the Vintage album,

because they would've put it out anyway, with or without me. They were

gonna put it out as a bootleg. There was no way I could stop them."

So he joined them - after one desperate attempt at sabotage. He had

given Together a set of mix masters, keeping the original tapes himself.

"I went to their studios," ostensibly to identify tapes for MGM. "I

looked at each box, and I had a big magnet with me and erased the

tapes." To no avail. "They had quarter-track dubs made, too, and they

were going to release those." Still, he contributed the liner notes for

the Vintage album. He said he refused to do anything on the second one,

which carries no information on recording dates or places.

"We had no liner information," Sunflower's Sidoti claimed, "because we didn't want to take away from the artwork."

Sidoti said he couldn't help Cohen point fingers. "There was nobody

involved in the Dead albums from the executive standpoint," he said.

"This was a deal made by Together and we just picked up the contract.

When Together was disbanded or whatever, the tapes were laying around in

the Transcontinental office, and Mac Davis [the veteran songwriter and

president of the eight-month-old Sunflower label] bought the tapes from

Transcon."

Transcontinental Investment Corporation is the holding group that formed

Transcontinental Entertainment Corporation and hired young Mike Curb,

now president of MGM Records, to be its head. Curb in turn, hired Gary

Usher to form "an avant-garde artist-oriented record label, a division

of TEC," as Usher put it. "They made a lot of promises - $1 million to

work with, total autonomy, and a three-year minimum. TEC owned 40

percent of the racks in the country; they had lots of money." Usher had

been successful with the Beach Boys, co-writing some tunes with Brian

Wilson, as well as with the Byrds and Chad and Jeremy (as a producer).

He was looking to do something different.

"I always wanted to do a series called 'Archives.'" In fact, Together

put out two interesting collections, one of the Pre-Flyte Byrds, and one

of various L.A.-area artists and bands. "Pre-Flyte sold well, it got

the company off, and other people started bringing me tapes - Lord

Buckley and good material like that." That's when he told Howard Wolf

about "Archives" and sent him off to San Francisco.

But six months into Together's existence, Usher said, "Transcon started

fudging with money, saying, 'We think the San Francisco scene is

bullshit and we don't know who Howard Wolf is.' [Wolf, Usher said, had

been advanced $5000 on the project.] I took Howard over there, he

explained it, and they bought the idea of one full album from the

Grateful Dead." Transcon stock then dropped, Usher said, and Curb split.

"I simply walked out of there and went to RCA. I signed all my rights

and interest over to TEC, who then sold out of the record business, and

MGM took over all the properties."

So now you have MGM Records, whose president had so loudly announced a purge of all MGM artists who "advocate and exploit drugs," squeezing out every acidic second of Grateful Dead music that they can.

Sidoti says Sunflower is "a solely-owned label owned by Mac Davis." But

MGM, it says on the liners, manufactures and distributes, and even the

lion head appears on the two Dead albums. "Well, it's a joint venture

with MGM." Watch your choice of words.

"Mike Curb has nothing to do with it," Sidoti continued. "There's lots

of controversy surrounding whatever he does. God bless Mike Curb,

whatever his thing is."

But how do you justify putting out shit and misrepresenting a group at the same time?

"There was no motive of hurting the Grateful Dead," Sidoti said. Earlier

in our conversation - and this helps explain the motive - he had said,

"Since the first one sold well, we decided to go ahead with another. We

had four masters left over - they were decent tapes. There were a lot of

dropouts on the tape, but we got rid of all those. I really think this

helped the group. Actually the record buyer would have to be a Grateful

Dead freak to be interested, and there's an X amount of people who

otherwise couldn't buy the LP and compare."