1960s Folksinger Danny Cox was hardly a major figure, but he did have a career in music, which is every musician's goal. Cox was born in Cincinnati, and had released a few albums in the early 1960s. Around 1967, he moved to Kansas City. Cox released a few albums in the late 60s and early 70s. In the narrow universe of Grateful Dead history, Cox's place is that during 1970 demo sessions at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco, John Kahn and Merl Saunders played on the recordings. During the sessions, Kahn introduced Jerry Garcia--recording in another room at Heider's--to Merl Saunders, and an important partnership was born.

Cox's fifth album, Live At The Family Dog was released in 1970. Recording details are scant. If, in fact, the album really was recorded at the Family Dog, then the odds are very high that the source tape for the album was recorded by Owsley Stanley himself. Cox only played Chet Helms' Family Dog on The Great Highway on two consecutive weekends. On one of those weekends, Danny Cox opened for the Grateful Dead for two nights, and Owsley made his usual excellent tapes of the Dead. So the odds seem pretty reasonable that Cox was recorded by Owsley on one or both of those nights, and those tapes might have been turned into the 1970 Live At The Family Dog lp. So we may have a secret lost Owsley tape. Or maybe not. Let's review.

[update: we have a definitive answer that Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog was not recorded by Owsley, delicious as that theory was. See below]

The Family Dog on The Great Highway, 660 Great Highway, San Francisco, CA

The Family Dog was a foundation stone in the rise of San Francisco rock, and it was in operation in various forms from Fall 1965 through the Summer of 1970. For sound historical reasons, most of the focus on the Family Dog has been on the original 4-person collective who organized the first San Francisco Dance Concerts in late 1965, and on their successor Chet Helms. Helms took over the Family Dog in early 1966, and after a brief partnership with Bill Graham at the Fillmore, promoted memorable concerts at the Avalon Ballroom from Spring 1966 through December 1968. The posters, music and foggy memories of the Avalon are what made the Family Dog a legendary 60s rock icon.In the Summer of 1969, however, with San Francisco as one of the fulcrums of the rock music explosion, Chet Helms opened another venue. The Family Dog on The Great Highway, at 660 Great Highway, on the Western edge of San Francisco, was only open for 14 months and was not a success. The Family Dog on The Great Highway was smaller than the Bill Graham's old Fillmore Auditorium. It could hold up to 1500, but the official capacity was probably closer to 1000. Unlike the comparatively centrally located Fillmore West, the FDGH was far from downtown, far from the Peninsula suburbs, and not particularly easy to get to from the freeway. For East Bay or Marin residents, the Great Highway was a formidable trip. The little ballroom was very appealing, but if you didn't live way out in the Avenues, you had to drive. As a result, FDGH didn't get a huge number of casual drop-ins, and that didn't help its fortunes. Most of the locals referred to the venue as "Playland."

October 31, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Danny Cox/Alan Watts/Golden Toad/Hells Angels Own Band (Friday)

November 1-2, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/Danny Cox/Golden Toad (Saturday-Sunday)

The Grateful Dead played Halloween 1969 at the tiny Student Union Ballroom at San Jose State, but they played the Saturday and Sunday of that weekend at the Family Dog. Danny Cox opened the shows at The Dog, along with the unique Golden Toad, led by Owsley pal Bob Thomas. Owsley recorded the Grateful Dead at the Family Dog on November 1 and 2. It's fairly plausible that Owsley recorded Danny Cox, as he regularly recorded opening acts.

we recently confirmed that Owsley did not record Danny Cox at the Family Dog because Cox's manager, Howard Wolf, would not let him tape any acts that Wolf managed. We learned this from the dedicated house tech at the Family Dog at the time, Lee Brenkman, currently a faculty member at the California Jazz Conservatory. Lee believes the live Danny Cox recording that was released actually came from the Hell's Angels Halloween party, and adds that it was the last calm thing that occurred that night.[for more about Howard Wolf, see below]

November 7-9, 1969 Family Dog on The Great Highway, San Francisco, CA: Velvet Underground/Danny Cox/John Adams (Sat-Sun only)/Maximum Speed Limit (Friday-Sunday)

The legendary Velvet Underground played the next weekend at the Family Dog, prior to a three-week booking at the Matrix. Law student and guitarist Robert Quine, a friend of the band, taped just about all the shows with his cassette recorder. Some of the Family Dog tapes were released on a 2001 Polydor Records box set called as The Velvet Underground Bootleg Series, Volume 1: The Quine Tapes (sadly, there never was a

volume 2). While Quine recorded all the Velvet sets, there's no evidence (nor likelihood) that he would have recorded any opening acts. Also, the tapes would have been kind of crude, and not suitable for release in the 60s. I suppose it's not unthinkable that someone else recorded Cox on this weekend, but it's highly unlikely.

|

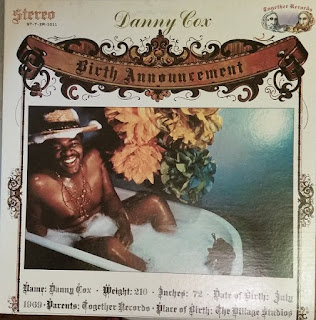

| Danny Cox's 3rd album was Birth Announcement, a double-LP released on Together Records in 1969 and produced by Gary Usher |

Danny Cox (b. 1943) was from Cincinnati, but he had relocated to Kansas City in 1967. Cox, a large African-American man, defied rather conventional 60s expectations by singing folk music instead of blues. Danny Cox's debut album was At The Seven Cities, released in 1963. His next album, Sunny, on Pioneer Records, was not released until 1968. When Cox played at the Family Dog, his current album was his 3rd, Birth Announcement, a double-lp on Together Records produced by Gary Usher. On the album, Cox sang folk classics along with Beatles and Dylan songs, lightly backed.

In 1970, Cox shared management with Brewer And Shipley, and like them he would record an album for ABC/Dunhill in San Francisco with producer Nick Gravenites. Recorded at Wally Heider Studios, it was released in 1971. In between 1969 Birth Announcement and his 1971 ABC/Dunhill albums, Sunflower Records released Live At The Family Dog. We know almost nothing about the Family Dog record save for the listings in Discogs.com (linked).

|

| Preflyte, Byrds recordings from 1965, was released on Together Records in 1969 |

Together Records>Sunflower Records

Back in 1969 and 1970, there was a lot of money to be made selling records. A lot. Most of it didn't go the artists or the songwriters, sure. But a lot of money was made. Why do you think there were so many albums released by bands you never heard of, who maybe played the Fillmore once, and disappeared? Because on the whole, those records made money. Outside of big cities and a few big college towns, there weren't even dedicated record-only stores. Most albums were sold at department stores, drug stores, musical instrument stores and other general merchandise places. The store would have a few hundred albums for sale, not all of them hits. If you had already bought the last Beatles album and wanted something new, you flipped through the racks until something caught your eye. Of course you hadn't heard it--radio was terrible. But if it had a cool cover and the song titles were interesting, why not? So those racks were filled up with quickie albums.

Together Records had released Danny Cox's 1969 double album, Birth Announcement. Together was a new label, started by producers Gary Usher, Curt Boettcher and Keith Olsen (yes, the future Grateful Dead producer). Usher 1938-90) had produced some surf hits (like "Go Little Honda") and some Byrds albums, like 1968's great Sweetheart Of The Rodeo. Together's best known release was Pre-Flyte, an album of Byrds recordings that pre-dated the band's signing with Columbia. Remember, in 1969, there were only a few Byrds albums, and no cassette tapes circulated, so if you wanted some more Byrds, you took what you could find in the Macy's rack.

|

| Vintage Dead, recorded at the Avalon Ballroom in 1966, and released on Sunflower in 1971 |

Usher had a good idea, though. He approached former Avalon Ballroom soundman Bob Cohen about all the tapes he had recorded there in 1966, long before the bands were signed. The idea was to make a triple album of the Dead, Quicksilver, Big Brother, Steve Miller, Moby Grape and others from the very beginning. The concept was that the album would support the Family Dog itself. I wrote about this whole complicated story earlier. The summary of the story is that Together folded its tent, and Gary Usher sold out his contracts to Sunflower Records, a subsidiary of MGM. At that point, the only band that had agreed to the triple-lp was the Dead. Ben Fong-Torres wrote about it in Rolling Stone in 1971:

With the Dead set, all Together had to do was get releases from enough of the other groups, like Big Brother, Moby Grape, Steve Miller, Quicksilver, Great Society, and Daily Flash. The idea was a three-LP package.

But, Cohen said, "they had trouble getting those releases." Then, "all of a sudden I find out that in one day Together ceased to exist! To settle everything, Gary Usher should have told me to get my tapes; I assumed the deal was off. My tapes are sitting there. But when I try to get them, I can't. MGM bought them."

A year later, out of the blue, there's an album on the market, Vintage Dead, on another new label, Sunflower (with MGM Records taking manufacturing and distributing credits) - not an anthology but, rather, a Dead album featuring five cuts

Sunflower had released Vintage Dead in October 1970, with the legal rights but not the explicit permission of the Grateful Dead. As a fan at the time, this was the only window into the lost world of the early Dead, but the Dead themselves weren't very happy. But that was the record biz back in the day--the handling of the rights favored the label, not the artists, and once the band had agreed to sign, Gary Usher could sell Together Records contracts to Sunflower, and the band was stuck.

Gary Usher had produced Danny Cox's album on Together in 1969. Come 1970, Sunflower Records releases a Danny Cox album, produced by Gary Usher. It sure looks like a precursor for Vintage Dead. Yet why would Sunflower be releasing an album by Danny Cox--he had a following, yes, but nothing like the Grateful Dead. What could Sunflower have been thinking?

Since Sunflower probably wasn't going out of their way to pay Danny Cox, or anyone else, they didn't need to sell that many records to make a buck. Cox looked like a cool black dude, and the Family Dog, via the Avalon, had some hip credentials around the country.

The runout matrix (on the inner groove) suggests the album was pressed in September 1970, for release shortly thereafter. By that time, Sunflower would have known that Nick Gravenites was recording Danny Cox in San Francisco for ABC/Dunhill. So Together might have been hoping that ABC would push Cox, and that Live At The Family Dog would be the beneficiary. This was a common record company strategy in the day.

Sunflower had paid for Together's assets, and Danny Cox's recording was never going to make them any money sitting on the shelf--why not release it and hope for the best? Crooked or straight, that's what the record business was all about.

[Update]: It turns out that in 1969, Cox was managed by Howard Wolf. Wolf had been the booking agent for the Avalon Ballroom in the late 60s. Wolf was also the one who had brokered the deal between Gary Usher, Together Records and Bob Cohen (more complete details are here). So, presumably when Together Records' assets were sold to MGM/Sunflower, the Danny Cox recording went along with the material that would become Vintage Dead.

Did Owsley Record Danny Cox at The Family Dog?

The 1960s record business was full of strange deceptions, perpetrated by everyone involved. It was common practice in the 60s to release an outdated live album of a newly-popular artist, and slap a contemporary cover on it. The Chambers Brothers had been part of the folk circuit from the early 60s onwards. They recorded for the tiny label Vault Records. In late 1967, however, their souls got psychelicized, and the Chambers Brothers recorded the huge hit "Time Has Come Today" for Columbia. So in 1969 Vault released an earlier live recording, and called it Shout! The Chambers Brothers Live. Although it had been recorded around 1966 or so, Vault used a picture of the Chambers Brothers in concert at Frost Amphitheatre in Stanford University from Summer 1968. The album doesn't say where it was recorded, but it lets you draw the conclusion that it was a contemporary live album. Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog may be asking you to draw the same conclusion, that it was current when it was not.

If the recording is not from the Family Dog, the title may reflect another contractual issue. Artist contracts in those days controlled all their output, including live recordings. So it may have been in the commercial interests of Gary Usher and Together to represent these recordings as coming from a year when Together controlled Cox's output. Since Cox only played the Family Dog in 1969, that may have been a fig leaf to ensure that Together, and hence Sunflower, could claim that the recordings were controlled by them. If they had been recorded in 1968 or 1970, for example, the rights may have been different. But unless Cox (or ABC) could definitively prove otherwise, the release couldn't be blocked.

In 1970, the band Canned Heat, desperate for cash for various reasons, released an album called Live At Topanga Corral. The album was ostensibly recorded in 1966, back when the then-unknown band had played the tiny roadhouse in Topanga Canyon. In fact, it had been recorded in 1968 at the Kaleidoscope in Hollywood, but Canned Heat wanted to hide that from their record company and cash the check. Was Liberty Records fooled? Probably not. But how would you prove to a jury that a 19-minute Canned Heat boogie was definitely recorded in 1968 rather than '66? So the Cox recording may have been purposely bereft of any relevant recording details.

Still, there's at least a 50-50 chance that Owsley did indeed record Danny Cox when he opened for the Grateful Dead. According to Hawk at the Owsley Stanley Foundation, there's no record of the Cox recording in the Owsley vaults, and Hawk is certain that Owsley would not have sold the tape at that time. Nonetheless, the tape could be in the Grateful Dead vaults, as an "add-on" to a Grateful Dead reel. Also, per Hawk, Owsley might have shared the tape with the artist if he liked the performance. Given that Together Records, via Howard Wolf, was considering working with the Family Dog and the Grateful Dead, there would have been some social connections between the Dead organization, Owsley and Cox management.

Together collapsed around 1970, and sold out their assets to Sunflower Records. Given how Sunflower acted without concern for the artist in the case of Vintage Dead, there's every reason to think they would have acted similarly with Danny Cox. If Sunflower realized they had a good sounding live tape for an artist signed to another label, they would have released it. If the tape was from Owsley and he hadn't intended it for release, Sunflower wouldn't have cared. The writing on the matrix run-out (inner groove), from the pressing plant, says "SUN 5002 MGS 2420 15 Sept. '70 Ɛ.O." This suggests a September manufacture date for a release in Fall 1970, exactly the same schedule as Vintage Dead. If that was the case, since Owsley had been in San Pedro Correctional Facility since July, he was hardly going to notice the album in his local record store. Such cynical calculation was also typical of the record industry back in the day.

Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog--Sunflower Records 50002, 1970

My curiosity was too great, so I ordered the album, and it arrived on my doorstep. I have no special knowledge, I don't have golden ears. On the other hand, I've heard plenty of Owsley recordings, both of the Grateful Dead and other groups as well. I've also heard plenty of "board tapes" of 60s acts, the usual ones that circulate. Much as I enjoy all that material, there are plenty of circulating board tapes that are awfully tinny and wouldn't make great releases.

Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog isn't like other old 60s tapes. The recording has tremendous presence, as if you are at the venue. There's a big crowd, too (for a folk artist), and the sound doesn't sound dubbed in (another 60s trick). Sure, live albums recorded in the 80s and afterwards sound really good, but not many 60s tapes sound this good. The end of side 1 seems to be the end of a set, so probably the album is an edit of two nights, which makes sense.

Did Owsley record the tapes that were the basis of Live At The Family Dog? I have no facts or knowledge that I haven't stated here--and there aren't many--and we may never know the answer. But if you ask me to guess if the album is based on tapes recorded by Owsley, it sure seems likely to me. I don't think it was a coincidence that Sunflower Records released two Gary Usher projects in October 1970, so I have to think that Vintage Dead and Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog are intimately connected. Since we will probably never get other facts, you can decide for yourself. I'm voting for Owsley as the recording engineer.

Update: as I've pointed out above, my vote was plausible but incorrect. Since Cox manager Howard Wolf wouldn't let Owsley record his opening acts, the most likely result was that the Cox set was recorded on Halloween 1969, by some other party. With Owsley managing the soundboard for the rest of the weekend, it seems less likely that the Bear would let someone take over his board to record.

Danny Cox/Grateful Dead Summary

- Danny Cox opened two shows for the Grateful Dead on November 1 and 2, 1969 at the Family Dog on The Great Highway in San Francisco.

- It's possible that Owsley Stanley recorded Cox at the Family Dog, and his tape may have been the source for the album Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog, released on Sunflower Records in 1970

- Whether or not Owsley actually recorded Cox, Cox and the Grateful Dead had the unique experience of having a deal with Gary Usher and Together Records, only to have the material released on MGM/Sunflower. In the Dead's case (Vintage Dead) it was legal but not welcome--we know nothing about how Cox felt about the Sunflower release

- Around August 1970, Cox was recording at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco with producer Nick Gravenites, and his supporting musicians included John Kahn and Merl Saunders. Kahn took a moment to introduce Saunders to Jerry Garcia, recording in Heider's at another room. A month or two later, Saunders would join the pair at the Matrix.

|

| Track 4, side 2 of Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog is "Me and My Uncle" (Trad.-Arr. by Danny Cox) |

And finally, on the Live At The Family Dog album, Danny Cox performed his own arrangement of "Me And My Uncle," adding yet another strand to the elaborate history of the song (celebrated in both my blog and Jesse Jarnow's Deadcast episode).

|

| The back cover to Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog |

Danny Cox Live At The Family Dog

Tracklist

A1 Hang Down Blues Written-By – Cox* 4:06

A2 Keep Your Hands Off It Arranged By – Danny Cox Written-By – Trad.* 3:03

Medley (12:01)

A3a Universal Soldier Written-By – St. Marie*

A3b God Bless America Written-By – Berlin*

A3c Aquarius / Let The Sun Shine In Written-By – Ragni*, MacDermot*, Rado*

B1 Rake And Rambling Sailor Lad Written-By – Cox* 3:26

B2 Just Like A Woman Written-By – Dylan* 7:13

B3 Jelly, Jelly Arranged By – Danny Cox Written-By – Trad.* 5:32

B4 Me And My Uncle Arranged By – Danny Cox Written-By – Trad.* 3:25

Record Company – Sunflower Enterprises

Copyright © – Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.

Manufactured By – MGM Record Corporation

Recorded At – The Family Dog, San Francisco

Pressed By – MGM Custom Pressing Division

Distributed By – TRC (2)

Published By – Bealin Music Publ. Co.

Published By – Woodmere Music

Published By – Irving Berlin Music

Published By – United Artists Music

Published By – Dwarf Music

Credits

Producer – Gary Usher

Producer [Associate], Edited By, Mixed By [Remix] – Richard Delvy

.jpg)