|

An ad from the Oct 16, 1970 Berkeley Barb for upcoming shows at The New Orleans House. James and The Good Brothers "Courtesy Of The Grateful Dead" are booked for the weekend of October 23-24

|

James And The Good BrothersJames And The Good Brothers were a Canadian acoustic trio who were an extended part of the Grateful Dead family. Guitarist James Ackroyd had teamed with twin brothers Brian and Bruce Good, on guitar and autoharp, respectively. All sang, and their music was in a country-folk style, but without a pronounced Southern twang. The trio had met the Grateful Dead when they played on the infamous Festival Express cross-Canadian tour. The Dead invited them to San Francisco, and the group came down to San Francisco, where the Dead helped them get gigs.

James and The Good Brothers sang original songs, more or

less in the vein of Crosby, Stills and Nash or America. They were more

country than either of those bands, but since they had Canadian accents

rather than Southern ones, their music had a different resonance with American

listeners. Also, since the Good Brothers used an autoharp, a rarely used

instrument, their music had a different feel to it. It's no surprise

that James And The Good Brothers were signed to Columbia, since major label record companies were snapping up any band in the CSN vein.

According to Bruce and Brian Good, in a 2015 interview, they went into one of the "music cars" on the Festival Express train, and wound up picking with Garcia. They played bluegrass with him, and Garcia took a liking to them. Per Bruce, at the end of the train tour, the Dead would invite them to San Francisco record an album at their studio. Now, the story is a little more complicated than that, but for a broad brush 40-some years later, it was an accurate description.

James

And The Good Brothers would record at Wally Heider's with Grateful Dead

engineer

Betty Cantor. Jerry Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann likely played on the

initial sessions, although their tracks were not used on the final album.

Ultimately, parts of the album seems to have been re-recorded in

Toronto. Columbia would release the James And The Good Brothers album in

November, 1971.

By March, 1971,

however, the band had opened a weekend for the New Riders Of The Purple

Sage at Fillmore West (on February 25-28). When they had played there,

Jerry Garcia (pedal steel guitar), Jack Casady ("balalaika" bass) and

Spencer Dryden (drums) had joined the trio. Now, Garcia and Dryden were

playing with the New Riders that night anyway, but the fact that a trio of heavyweights

joined them got the band mentioned in a review. It also made their

status as Grateful Dead "family members" apparent.

Ultimately, James Ackroyd would

stay in California, and the

Good Brothers would return to Canada, where they had a successful

musical career along with their banjo-playing younger brother Larry.

Rock Music Economics ca. 1970: New and Next RidersIn early 1970, the Grateful Dead had been in dire economic straights. In March, 1970, they had fired their manager Lenny Hart because he had absconded with $150,000 of the band's money, an enormous sum at the time. Their previous studio album had run way, way over budget, so they weren't getting royalties from that. The recently-released

Live/Dead was promising, but it wasn't going to be any kind of conventional hit. All of the band members were functionally broke. Throughout 1970, under the guidance of road manager Sam Cutler, the Grateful Dead played there way back into solvency. Along the way, they had put out an album that was cheaply recorded and widely played on FM stations across the country. The album in turn increased concert receipts, so the Dead were finally doing pretty well. By the end of the year, band members had bought cars, and they had stopped living in overcrowded communal quarters.

The Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia did things in their own manner, but they always had an entrepreneurial streak. Unhappy with Bill Graham and Chet Helms, they had taken over the Carousel Ballroom in 1968. Though it had failed, they had nearly merged with Helms and his Family Dog in early 1970, until Helms had demurred at the idea of being in business with Lenny Hart. The Dead had also been instrumental in the formation of Alembic Engineering, creating a business where Ron Wickersham, Owsley Stanley, Bob Matthews and others could focus on high quality sound gear for live performance. Various other schemes had gotten floated over the years (google "Deadpatch"), even if they hadn't gotten off the ground. So Garcia and the Dead always had big schemes, even if they didn't go the way that they planned.

One of Jerry Garcia's unconventional enterprises was appearing as a sideman in a group completely separate from his main band. Garcia had been playing pedal steel guitar for the New Riders of The Purple Sage since Summer 1969. It was rare enough for rock stars to play outside their own group for more than a single recording session, but Garcia had a whole different band. The only real comparison was Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady in Hot Tuna, but Jorma and Jack led that band. Garcia actually played a different instrument in the Riders and let John Dawson be the frontman.

Still, Garcia's unorthodoxy had gotten the New Riders noticed. The Riders opened for Dead shows and played around the Bay Area, to the extent Garcia was available. By the Summer, Garcia knew that in order for the New Riders to thrive, they would need their full-time pedal steel guitarist, and he had spotted Buddy Cage. Cage was on the Festival Express tour playing with Ian and Sylvia Tyson's band Great Speckled Bird. Some sort of invitation resulted from the train trip, and Cage would join the New Riders in November of 1971, after relocating to the Bay Area.

I don't think Garcia reflected much on what he was doing, but I am confident that he was conscious of what he was trying to do. Unlikely as Garcia's efforts with the New Riders were in the world of hippie rock, they were pretty common in the worlds of jazz or country music. Plenty of jazz musicians would play around New York outside of their usual combos, bringing attention to lesser known musicians. Similarly, most jazz fans had bought a jazz album by someone they hadn't heard of just because another, more famous musician was on the record.

Generally, when a Nashville star toured, they usually brought along an ensemble of other singers and players, helping to build those careers. Porter Wagoner, a huge country star since the 1950s, had a singer in 1965-66 named Jeannie Seely, who was part of his show and duetted with him. No one really remembers her. But we all remember Dolly Parton, who replaced Seely in the Wagoner show (on TV and on tour) from 1966-74. So when the New Riders played on a Dead show, with Garcia in the band, there was an existing business model.

Other wings of the fledgling Grateful Dead enterprise were benefiting from the New Riders. Sam Cutler was organizing tours and booking shows, Jon McIntire was working with the record companies and Alembic was providing sound gear. With another band "in development," all these enterprises had a chance to benefit. In turn, those enterprises gave the New Riders access to people and equipment they would not have had without the Dead connection. So when Garcia invited James and The Good Brothers to come to San Francisco to help them make a record, he wasn't just being friendly--it was part of a plan.

Although only partly articulated, the pillars of the early 1970s Grateful Dead empire was built on three legs:

Generosity: at his core, Garcia was a generous man when it came to music and musicians. He didn't need much--a guitar, an amp, something to smoke, and a gig--and he was going to share what else he had. Garcia also implicitly realized that his status could help other musicians without any harm to his own future, so why not be generous? Garcia's attitude defined the entire Grateful Dead enterprise: if your own needs are met, look out for someone else.

Community: some parts of the Grateful Dead team were specifically interested in building community. Jon McIntire was an important voice here. Blair Jackson and David Gans quote him as saying his principal interest was in building community, not business (This Is All A Dream We Dreamed, p.214). The Grateful Dead grasped early that their own audience could be self-sustaining, if they were treated properly. In general, the Dead were interested in creating a tiny ecosystem where goods and services were largely supplied by an interlocking group of people. This could keep a lot of friends and family employed, without those people having to be musicians or have other rare skills. Old friends and band girlfriends could look after the warehouse or answer phones or any number of other roles, and they did.

Transactional: in order to function safely in the Capitalist world, the Grateful Dead had to thrive in it. Garcia, nor Cutler, nor McIntire, had no problem with any of this, beyond not wanting to wear a suit and tie. The businesses created by the Grateful Dead--, booking, tour management, recording studios, live sound equipment--still needed additional customers beyond the Dead. At the same time, the clients of these enterprises (Out Of Town Tours, Alembic, etc) benefited from the expertise of the likes of Sam Cutler, Jon McIntire or Ron Wickersham.

So when Garcia invited James And The Good Brothers to come to San Francisco, it went beyond a musician helping some guys he liked who were a bit lower on the ladder than he was. Garcia was providing fuel for the Grateful Dead economy to thrive, and James And The Good Brothers were going to benefit. I'm not imagining this--Garcia would do exactly the same thing a few months later when he invited David Grisman, Richard Loren and the Rowan Brothers to relocate from Manhattan to Stinson Beach. On a larger scale, these pillars were the thinking behind Round Records. Garcia didn't have to risk his capital on albums by bluegrass bands, Robert Hunter or electronic composers, but he did.

So the invitation for James And The Good Brothers wasn't just a generous suggestion by Jerry Garcia, but a test run of Garcia's new recognition that the success and fame of the Grateful Dead could be a magnet for the success of others. Thus, reviewing the performance history of James And The Good Brothers in the Bay Area isn't just archival, but a roadmap for Garcia to replicate his contribution to the New Riders on to another band, a Next Riders. It was only partially successful, but it was no less informative for that.

James and The Good Brothers: Canada 1970

Brian and Bruce Good were from Richmond Hill, Ontario, part of greater Toronto. They had formed a country-folk quartet called the Kinfolk with Marty Steiger and Margaret McQueen, playing traditonal country with a distinct Canadian flavor. They played the coffeehouses in Toronto and fairs in Ontario. By early 1970, two members of the Kinfolk had left (well, McQueen married Bruce, but she did leave the band).

The Good Brothers would meet guitarist James Ackroyd by chance in a Yorkville (Toronto) coffee shop called The Penny Farthing around February of 1970. Ackroyd, from Winnipeg, had been the lead guitarist in groups such as Barry Ennis and The Keymen and The Knack. The trio re-named themselves James And The Good Brothers. After playing around Ontario, the trio was then invited on the Canadian Express Train Tour with the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin and others

April 3, 1970 Maple Leaf Gardens, Toronto, ON Grand Funk Railroad/James and The Good Brothers

The band's initial performance was, apparently, opening for Grand Funk Railroad at the Maple Leaf Gardens. Presumably they also played other shows around Ontario. James And The Good Brothers had been advertised as part of the Festival Express Tour as early as May 4 (from a wire service article in the Los Angeles Times).

June 27-28, 1970 Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, ON Festival Express TourIt's unclear if James And The Good Brothers played one day at the stadium or on both.

June 28, 1970 Coronation Park, Toronto, ON (Sunday) Free Concert

The Grateful Dead agreed to play a free concert in a Toronto park on Sunday afternoon, between the paid shows, in order to assuage the feelings of hippies who thought music should be free. The Dead and The New Riders played, but it's unclear who else performed. Since James And The Good Brothers were an acoustic trio, it may have been easier for them to play the free show in the park.

After the Toronto show, the musicians boarded the infamous train, and the trio met Garcia during a bluegrass jam. Apparently the actual invitation to come to San Francisco was extended by Gail Hellund, who was sort of an operations manager (I'm not sure of her official title). Some evidence suggests that Hellund acted as the manager of James And The Good Brothers along with any Dead or New Riders duties. This would fit in with the model of cooperation and expansion outlined above. Gail Hellund's time and skills could be usefully distributed to another enterprise.

July 1, 1970 Winnipeg Fairgrounds, Winnipeg, MB (Wed) Festival Express Tour

July 4-5, 1970 McMahon Stadium, Calgary, AB (Saturday-Sunday) Festival Express Tour

By the end of the train trip, Ackroyd and the Good Brothers had been invited to San Francisco. Presumably the band played other gigs around Toronto until their Fall arrival in the Bay Area.

James And The Good Brothers in San Francisco, Performance Listing 1970-71

October 15, 1970 The Matrix, San Francisco, CA: James and The Good Brothers (Thursday) "Courtesy of The Grateful Dead"

Garcia's stature at the Matrix was such that a request by the Grateful Dead office to book an unknown out-of-town band would be accepted on its face. At the same time, it's worth noting that the Matrix wasn't booking premier club acts in any case. The most intriguing thing about the notation in the San Francisco Chronicle Datebook listings was that James And The Good Brothers are noted as "Courtesy Of The Grateful Dead." On one hand, this was unprecedented. On the other hand, the sort of tuned-in hippie who went to the Matrix would have heard of the New Riders, so they could probably guess a little about what was going on.

|

The Inn Of The Beginning, at 8201 Old Redwood Highway in Cotati, CA, as it appeared in 2010

|

October 16-17, 1970 Inn Of The Beginning, Cotati, CA: Cat Mother/James and The Good Brothers (Friday-Saturday)

Cat Mother And The All Night News Boys were a Greenwich Village folk-rock band who had been making their second album (Albion Doo-Wah) at Pacific High Recorders, and had simply decided to stay in the Bay Area. Pacific High Recorders was at 60 Brady Street, right behind the Fillmore West, and would be sold to Alembic in 1971, although they would continue to use the name Pacific High Recorders on occasion.

October 23-24, 1970 New Orleans House, Berkeley, CA: Redwing/James and The Good Brothers (Friday-Saturday) "Courtesy of the Grateful Dead"

Redwing was a Sacramento group that had evolved out of a popular

60s band called The New Breed. The best known member was bassist Tim

Schmidt, who by 1970 had joined Poco (and would later join The Eagles).

Redwing had made an album in 1970 for United Artists, and some of their

material had also been released under the band-name Glad.

October 26, 1970 Lion's Share, San Anselmo, CA: Janis Joplin's Wake (Monday)

Janis Joplin had died the night of October 5, 1970. As part of her will, she had a gigantic party thrown for her at the Lion's Share in San Anselmo. The Lion's Share was another musician's hangout, and about 10 minutes from downtown San Rafael. The Grateful Dead flew back from the East Coast to perform. In the 2015 interview, Bruce Good mentioned how honored they were to be invited. They had become friendly with Janis on the Festival Express train.

Every hippie in the Bay Area would have wanted an invite to Janis' wake, but James And The Good Brothers actually went. The fact that they got invited was a clear, if sad, indicator that they were part of the extended Grateful Dead family. I don't know if the band actually played, but it's entirely plausible they got up and sang a few songs (and plausible that no one, including the band, remembers for sure).

October 27-November 1, 1970 Troubadour James and The Good Brothers/Alliotta Haynes (Tuesday-Sunday)

I have found no dates for James And The Good Brothers in November. Both Brian and Bruce Good had family in Canada, so it's possible that they took a trip back home.

|

The Lion's Share, at 60 Red Hill Avenue in San Anselmo, sometime in the early 1970s

|

December 4-5, 1970 Lion's Share, San Anselmo, CA: James and The Good Brothers /The Pipe (Friday-Saturday)

December 11-12, 1970 Inn Of The Beginning, Cotati, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Pamela (Friday-Saturday)

James And The Good Brothers returned to headline a weekend at the Inn Of The Beginning. They must have been good enough in October for the Inn to give them a chance to co-headline a weekend. Sonoma State College was probably out of session, so it would have been a less high-profile night, but coming back to a club two months later as a weekend headliner was still a healthy sign for the trio.

Co-headliner Pamela was almost certainly Pamela Polland. Polland was a singer-songwriter who had moved to Mill Valley after she had been signed to a solo contract by Columbia. Previously, she had been in a Los Angeles duo called Gentle Soul, who had released an album back in 1968. Polland's story is quite interesting (some readers may recognize her subsequent persona "Melba Rounds"), but it's mostly a sidelight to James And The Good Brothers.

In one post

Sward described what faced local singers who weren't in a loud rock band:

Gigs in Bay Area coffeehouses were easy to get, but they didn’t make a

lot of money for anyone, including the performers. They were able to get

a few gigs in clubs at 8 or 8:30 p.m., prior to when many rock bands

began setting up for a 9:30 show. I told club owners that my band would

help warm up the audience, didn’t need a big stage setup (no drums, no

big amps, no stage monitors) and would make them enough extra bucks

selling drinks to pay us.

However rock fans and acoustic music

fans didn’t always mix well. More often than not the audience would

start getting impatient around 9:15. “We want Jerry (Garcia); we want

Elvin (Bishop) and so on.”

I attended a lot of Lamb gigs and saw

such other Bay Area acoustic performers as Lambert & Nuttycombe,

Jeffrey Cain and Uncle Vinty. They were all bucking up against rock ‘n

roll. The audiences for rock bands were larger; and that meant more

money for the club owners.

Sward went on to find unique bookings for her acts, and helped them record as well. Still, her reflections point up an historically unnoticed barrier for James And The Good Brothers. In the 60s and 70s, San Francisco was renowned for breaking new and interesting bands: Jefferson Airplane, The Dead, Big Brother, Sly and The Family Stone, Santana, Tower Of Power and the Doobie Brothers, to name the most prominent. While those groups were not confined to a single genre, they were all loud, danceable bands that could rock the Fillmore and Winterland.

Starting with the August 1969 release of the Crosby, Stills and Nash album, listeners, radio and record companies expanded their tastes to include rock musicians who, while writing original songs, were quieter. The new breed of singer/songwriters emphasized sincerity, acoustic guitars and sophisticated harmonies. James And The Good Brothers fit right into the vein that would lead groups like America and Seals And Crofts to huge success. A parallel success story at the time was The Band, whose first two albums sold well and got perhaps the best reviews any rock bands ever received. James And The Good Brothers were Canadian, too, so in acoustic way they evoked The Band's countrified harmonies.

Musicians from all over America had been coming to San Francisco to make it since the mid-60s, and James And The Good Brothers had relocated along with man others. It turned out, however, that for all its openness, early 70s San Francisco was a terrible place to break acoustic acts.

Singer/songwriters who played the Troubadour in West Hollywood did great, but acoustic trios didn't make it out of San Francisco. Diane Sward, for one, had figured this out and was trying to crack the egg, but in the end San Francisco wasn't a good place for acoustic bands. But James And The Good Brothers, nor the Dead's management, would not find that out until later.

December 18, 1970 Burbank Auditorium, Santa Rosa Junior College, Santa Rosa, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Victoria/Tim and Jan (Friday)

The Junior College system in California was an outgrowth of both the GI Bill and the massive migration to California during and after World War 2. With numerous ex-GIs able to afford college, and a big population, California had to expand its college options. Not only did the University of California expand, and the State College system, too, but just about every county had a 2-year junior college with open admissions. Residents over 18 could go to college locally, effectively for free, and if they succeeded they could transfer to the State College or UC Systems.

In the case of Santa Rosa Junior College, it had existed since 1918, but had fully integrated into the State Junior College system by 1969. It was located downtown at 1501 Mendocino Road. Santa Rosa is in Sonoma County, 50 miles North of San Francisco.

A breathless article in the December 17, 1970 Oak Leaf, the Santa Rosa Junior College student newspaper, gives the band the full push (article courtesy of JGMF-transcribed as published)

The Christmas seasons festivities will begin tomorrow in Burbank Auditorium at 4.p.m when the student body of this campus will have the opportunity to hear three farout Canadians who call themselves JAMES AND THE GOOD BROTHERS.

Their manager, Gail, met them on the Festival Express while on a tour of Canada last summer, with the Grateful Dead and persuaded them to give California a go.

The first performance of James and The Good Brothers was two months ago at the Inn Of The Beginning. The audience response was so enthusiastically overwhelming that they are currently in the process of recording their first album.

According to one of the college sponsors of the group, the Grateful Dead, Eric Anderson, Gordon Lightfoot and countless others, who have heard James and the Good Brothers really freak out when they hear them.

The article goes on to say that the show's ticket sales will not even cover the costs, a sign that the school was dipping into its entertainment budget for this. In the early 70s, even Junior Colleges had entertainment budgets, and local bands could be the beneficiaries. It's likely that the fact that all three acts were acoustic, rather than full-out rock and roll, made them more palatable to the college. Tickets for the show were available at the Inn Of The Beginning, so it suggests that the Inn helped Gail Hellund book the band. Now, while I find it pretty likely that Gordon Lightfoot liked James and The Good Brothers, I doubt he would "really freak out" when he heard them. One can't help but suspect that a Mr. Rock Scully was helping to explain things to an eager cub reporter.

Although some comments in the article need to be taken with a grain of salt, note that there is already talk of a James And The Good Brothers album. At this exact moment, artists like James Taylor and Cat Stevens were hitting it big, so record companies would have been very interested in their sound. At the same time, the Grateful Dead had just released American Beauty, and with two hit albums in a row, their sponsorship of the band would mean a lot more to a record company.

Opening act "Victoria" (Victoria Domagalski) was a singer-songwriter, also part of the Bill Graham stable. Her debut album, Secret Of The Bloom,

had been released on Graham's San Francisco Records label (distributed

by Atlantic) in 1970. Victoria was a solo singer/songwriter, and one of

the acts often booked by Diane Sward as part of her acoustic packages.

December 31, 1970 Winterland, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/Hot Tuna/New Riders of The Purple Sage/James and The Good Brothers (Thursday)

January 21, 1971 Freeborn Hall, UC Davis, Davis, CA: Grateful Dead/New Riders of The Purple Sage/James and The Good Brothers (Thursday)

The Grateful Dead played on a Thursday night at UC Davis, just outside of Sacramento. They were joined by both the New Riders and James and The Good Brothers. While the Dead no longer did the acoustic set and the full "An Evening With The Grateful Dead," they were providing four sets with an acoustic opener.

January 27-28, 1971 Keystone Korner, San Francisco, CA: Big Brother and The Holding Company w/Nick Gravenites/James and The Good Brothers/Gideon and Power (Wednesday-Thursday)

Big Brother and The Holding Company had disintegrated at the end of 1968 when Janis Joplin left the band. Still, the band had reformed at the end of 1969, with the four original (pre-Janis) members and guitarist David Schallock (although James Gurley and Peter Albin had switched to bass and guitar, respectively). They had released a good, but unnoticed album on Columbia in 1970 called Be A Brother. Nick Gravenites was their producer and sometimes sang with them. They were still a name around the Bay Area, but no longer a major act.

Keystone Korner was mainly a blues club, although the actual bookings ranged from white rock bands to soul to Chicago blues. Still, just about all the acts were loud and bluesy, and in that respect, James And The Good Brothers may have been a little out of place.

Gideon and Power was a sort of Gospel-Rock band featuring singer Gideon Daniels. He would release one album in 1972, and Gideon and Power became a sort of farm team for the Elvin Bishop Group. In later years, Gideon and Power would include backup vocalist Mickey Thomas and organist Melvin Seals, both of whom would join Elvin Bishop sometime later (and then Jefferson Starship and Jerry Garcia Band, respectively).

January 29-30, 1971 Inn Of The Beginning, Cotati, CA: Lamb/James and The Good Brothers (Friday-Saturday)

Lamb had initially been a songwriting duo featuring singer and pianist Barbara Lamb and guitarist Bob Swanson. They were another act managed by Diane Sward, and this booking fit her idea of pairing acoustic acts in nightclubs. I think Lamb had a bass player and a drummer by this time, but I'm not sure of that.

I think by this time James And The Good Brothers had been signed to Columbia and started recording. The absence of any shows in the next month, plus some other clues, suggest that the band recorded throughout the month of February. Their Columbia album would be released in November, 1971. The producer was long-time Grateful Dead engineer Betty Cantor. She shared the engineering duties with Bob Matthews, so the Dead had assigned the A-Team that had delivered Live/Dead and Workingman's Dead. Initial recording took place at Pacific High Recorders, at 60 Brady Street behind the Fillmore West. Later, the studio would be purchased by Alembic and used primarily for mixing.

In late 1970, Columbia Records had signed the New Riders Of The Purple Sage. Columbia boss Clive Davis was high on Garcia (to coin a phrase). He had apparently tried to sign the Grateful Dead when their contract had come up in 1969, but Lenny Hart had extended the Warner Brothers deal for a few more albums. Davis was playing a long game, though. In his cosmology, the key to the Grateful Dead was Garcia--he wasn't wrong--so Davis took numerous steps to show Garcia favor. Not only did Davis sign the New Riders, a Columbia imprint (Douglas Records) had also signed Howard Wales to do an album. Columbia had also helped finance Mickey Hart's studio, according to Billboard.

On one hand, we can see Columbia's signing of James And The Good Brothers as a continuation of Clive Davis' ongoing efforts to make Garcia feel wanted when the Dead's contract renewal came up. Although the Dead surprised everybody by going it alone in '72, when Grateful Dead Records crumpled a few years later, Clive Davis--by now running Arista Records--finally got his opportunity. It took a while, but eventually the Grateful Dead had a massive hit with In The Dark, and sold a lot of other albums in between. So whether or not Garcia specifically recommended James And The Good Brothers to Clive Davis, we know that Davis had a vested interest in making Garcia see him favorably.

In 1970 and '71, Clive Davis signed the New Riders, James And The Good Brothers and the Rowan Brothers, all San Francisco bands with intimate ties to Jerry Garcia. In 1976 he got his man. Yet, to give Davis credit, he was also a pretty good record man. For one thing, the first four New Riders albums were pretty successful (NRPS, Powerglide, Gypsy Cowboy and Panama Red). Certainly Columbia turned a profit on those albums. So whatever Davis' motives for signing the Riders, it turned out pretty well financially for Columbia.

As for James And The Good Brothers, they were not really a success and broke up in 1972, as we will see. Afterwards, however, Brian and Bruce Good returned to Canada and teamed up with their younger brother Larry, and had a pretty successful career in Canada. So when Clive Davis had signed them in late 1970, he must have heard the talent and appeal. In that sense, Davis' signing of the band was retroactively justified by the Good Brothers' ultimate Canadian success. So while Garcia's "sponsorship" was essential for getting James And The Good Brothers' signing to Columbia, their own talent ultimately proved that the commercial sense of that investment, even if Columbia itself didn't benefit.

As for the album itself, I am pretty sure that Columbia was not pleased with the finished product, and took James And The Good Brothers to Toronto to re-record some different songs, without Bob and Betty. Contractually, Betty Cantor's name had to be on the album, but the record company seems to have overruled her mixes. Some cryptical details suggest that Jerry Garcia probably played on the initial sessions, but I suspect that any tracks that he played on were re-recorded in Toronto.

February 5-6, 1971 New Orleans House, Berkeley, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Abel (Friday-Saturday)

|

A picture and listing from the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat of February 15, 1971 for the Saturday night (February 20) show at the Veterans Memorial

|

February 20, 1971 Veterans Memorial Building, Santa Rosa, CA: Bronze Hog/Cat Mother and The All-Night Newsboys/James and The Good Brothers/Abraxas Rising (Saturday)Ace researcher David Kramer-Smyth found this date. All of these bands were local. Bronze Hog were effectively the "house band" at Inn Of The Beginning.

February 25-28, 1971 Fillmore West, San Francisco, CA: New Riders of The Purple Sage/Boz Scaggs/James and The Good Brothers (Thursday-Sunday)By early 1971, the Fillmore West was as legendary as ever, but it was starting to become too small for the booming rock market. Fillmore West's 2500-capacity had been 60% larger than the original Fillmore, but Winterland was over twice as big as the Fillmore West. Bigger bands didn't headline the Fillmore West as often as they had. They would still play for Bill Graham, but at bigger local venues.

At this time, the New Riders of The Purple Sage did not have an album. Save for some brief radio broadcasts, and a few demos on KSAN, the only people who had heard the New Riders had seen them in concert. Of course, Jerry Garcia was still their pedal steel guitar player. Boz Scaggs had released a fine debut on Atlantic in 1969, and he had a new release (Moments, on Columbia) coming out in March. So Boz was known, but he wasn't yet a major artist either. Thus the 4-day weekend at the Fillmore West was not anchored by acts that were currently big hits, either on FM radio or on tour.

One of these Fillmore West shows was written up in the suburban Hayward Daily Review by "KG", the team of Kathie Staska and George Mangum. The duo probably saw the Saturday (February 27) show. The most remarkable detail of the review was that James And The Good Brothers were joined by Jack Casady on "balalaika bass," Spencer Dryden on drums and Jerry Garcia on banjo. For one thing, the rhythm section would have helped the band go over in a rock hall like Fillmore West.

For another, Garcia's presence means that he knew the songs, so he must have been around for the recording of the album, or at least some of it. This public performance is the key reason that I think Garcia played on the album sessions. He is thanked on the album, but not listed in the credits. On the other hand, the tracks with Toronto musicians include a banjo player (younger brother Larry Good), which is why I think the tracks with Garcia were re-recorded. The album would not come out for another 8 months, so Clive Davis must have been unhappy with the results. I should add that in such circumstances, record company complaints were generally oriented toward the actual sound of the recording--particularly focused on how it would sound on the radio--rather than the musical quality itself. To a record guy, if the sound wasn't right, it wouldn't matter how Garcia or anyone else played on the tracks.

There's every reason to assume that Garcia played with James And The Good Brothers all four nights at Fillmore West. Thus Garcia was following the model of the New Riders, playing with them to let them benefit from the glow of his status. Garcia would do the same a few months later with the Rowan Brothers, playing a few local gigs and then joining them for their Fillmore West show when they opened for the Grateful Dead. The Rowan Brothers had also been signed to Columbia by Clive Davis. Was it a coincidence that Garcia played a similar role for all three Columbia bands? I doubt it.

March 7, 1971 Burl Theater, Boulder Creek, CA: Commander Cody and The Lost Planet Airmen/James and The Good Brothers (Sunday) 2pm show

By 1971 Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen were a popular local band, and had probably already been signed to Paramount Records. But they had not yet recorded their debut album (it would be released in November '71), so the Airmen weren't that well known outside of the East Bay. Cody and his crew had already played with the Dead and New Riders many times, however, so linking up with James And The Good Brothers was pretty logical.

Boulder Creek is on Highway 9 in the Santa Cruz Mountains, 13 winding miles from downtown Santa Cruz, about halfway to Saratoga. I don't know anything about the Burl Theater, but since Boulder Creek is in a forest of Redwood trees, it's easy to guess. At the time, the area was full of hippies, loners, bikers, pot growers and other peculiar characters. Many of the residents would have fit more than one of these categories. The show was booked for 2pm, leaving plenty of time for the band to get to Berkeley for their show later that evening.

March 7, 1971 Mandrake's, Berkeley, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Lizard (Sunday)

Mandrake's, at 1048 University Avenue in Berkeley, was near the corner of University and San Pablo Avenue, nearly two miles from campus. During World War 2, with the Oakland and Richmond shipyards booming, tired workers with money in their pockets needed to relax. San Pablo Avenue was known as "Music Row," with clubs from one end to another. Mandrake's was a remaining legacy. The 200-seat room had opened in 1965, initially a pool hall that sometimes booked music. It focused on blues and jazz, initially, but rapidly expanded to include rock. The little club served beer, wine and food, and was a good place for bands to build an audience.

March 10-11, 1971 Mandrake's, Berkeley, CA: Cat Mother/James and The Good Brothers (Wednesday-Thursday)

March 12-13, 1971 New Orleans House, Berkeley, CA: Cat Mother/James and The Good Brothers (Friday-Saturday)

Cat Mother, a much more established band, played four nights in Berkeley, supported by James And The Good Brothers. The two clubs were about a half mile apart, both on San Pablo Avenue.

|

The Boarding House, at 960 Bush St in San Francisco

|

March 26-28, 1971 Boarding House, San Francisco, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Melissa (Friday-Sunday)

The Boarding House was at 960 Bush Street (at Taylor), and I have written about its opening at some length. The Boarding House was an important club for the San Francisco music scene throughout the 1970s. In this initial version, however, the club was in the same space as The Troubadour, a downstairs dining room with long tables and a stage at one end, seating about 225. Most Bay Area rock fans from the era recall something different. That is because somewhere around 1972, Allen moved the club upstairs into what was initially called "The Boarding House Theater." The Theater was an elegant bowl-shaped room, with great sightlines and good sound. It had the same address, though, so the shows that we all recall are from the upstairs room, not the downstairs one. The downstairs room was still occasionally used for comedy during the later era.

April 2, 1971 Inn Of The Beginning, Cotati, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Loose Gravel (Friday)

April 3, 1971 Inn Of The Beginning, Cotati, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Clover (Saturday)

James And The Good Brothers returned to the Inn Of The Beginning. On Friday night, they were paired with Loose Gravel, a band led by former Charlatans guitarist Michael Wilhelm. On Saturday night, it was the Marin band Clover. At the time, Clover was a quartet led by guitarists John McFee and Alex Call. They would release two albums on Fantasy (their 1970 self-titled debut and 1971's Fourty Niner) before they were dropped.

April 6-11, 1971 The Boarding House, San Francisco, CA: James And The Good Brothers/Jo Ellen Yester (Tuesday-Sunday)

Things must have gone well in March, because James And The Good Brothers returned for another week.

April 29, 1971 Ives Hall, Sonoma State College, Rohnert Park, CA: Rick Taylor/CiCi/James and The Good Brothers/Lamb Peace Week Folk Festival (Thursday)

May 29-30, 1971 Winterland, San Francisco, CA: Grateful Dead/New Riders of The Purple Sage/RJ Fox/James and The Good Brothers (Saturday-Sunday)Bill Graham had recaptured the rights to Winterland, and he had booked the Dead to headline two shows on Friday and Saturday, May 28-29. Support acts were the New Riders Of The Purple Sage, James and The Good Brothers and RJ Fox. Once again, this was effectively another Evening With The Grateful Dead, with the exception that James And The Good Brothers were doing the acoustic set, instead of Garcia and Weir.

Thus the entire booking was part of the Grateful Dead "Family." RJ Fox was present courtesy of Crosby and Barncard, but those two were family members if anyone was. As it happened, Garcia fell ill. The Friday, May 28 show was canceled, and the shows were moved to May 29 and 30 (Saturday and Sunday). Garcia did not play with the New Riders on Saturday night, a sign of how poorly he must have felt [

update: as noted by LIA in the Comments, while James And The Good Brothers were advertised, they may not have played either night].

I have been able to find no James And The Good Brothers bookings from June through August. My assumption is that the band returned to Toronto to re-record parts of the album. Of course, since the Good Brothers were from Toronto, they probably had a vested interest in spending a few months there. Based on the credits, at least three tracks seem to have been recorded (or re-recorded) in Toronto.

update: David Kramer-Smyth is on the case

July 27-31, 1971 Le Hibou Cafe, Ottawa, ON, Canada: James And The Good Brothers (Tuesday-Sunday)

Remarkably, DKS also found the Fictitious Business Name Statement for James And The Good Brothers, published in the Santa Rosa Press-Democrat of August 1, 1971. The address given is 8201 Old Redwood Highway, the site of the Inn Of The Beginning. IOTB manager Ward Maillard is listed as their manager. This tells us when the band had to "get serious" as a California business, with an album on the way.

|

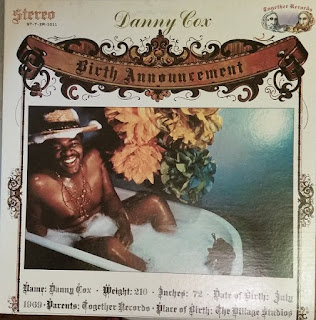

The James And The Good Brothers album was released on Columbia in November 1971

|

September 5, 1971 Pacific High Recorders (Alembic Studios), San Francisco, CA: James and The Good Brothers (Sunday)James And The Good Brothers reappeared in San Francisco, broadcast live on KSAN-fm, the biggest rock station in Northern California. At this time, KSAN had a regular Sunday night show where rock bands would perform live in the studio. KSAN supremo Tom Donahue would announce the studio as Pacific High Recording (at 60 Brady), but in fact by this time it was actually called Alembic Studios. I don't know exactly why there was this subterfuge, but I assume that Alembic did not want to attract attention, so that riffraff would not come to the studio "looking for Jerry." By using a name that didn't exist, it added a layer of obscurity to the location.

The weekly KSAN broadcasts have been the source of many great tapes from the era (

Deadheads will be most familiar with the February 6, 1972 KSAN broadcast with Merl Saunders). On this particular night there were three bands. The headliner, so to speak, was Van Morrison, who played a 90-minute set with his band that was for the ages. The highlight was a cover of Bob Dylan's "Just Like A Woman" which was played on KSAN regularly for the next decade. The middle act was Joy Of Cooking, a Berkeley band with a good album on Capitol.

While KSAN controlled the broadcasts, there were always complicated record company politics behind the scenes. We don't know what they were of course, but considering that James And The Good Brothers did not have an album, their presence couldn't have been a coincidence. Of course, they were signed to Columbia and managed by the Grateful Dead organization. So whether there was an explicit quid pro quo (such as Columbia purchasing ads) or just some mutual backscratching, connections count.

For us, however,

the high quality 53-minute tape gives us a clear picture of how James And The Good Brothers sounded. The band has nice harmonies and an easy flow, and they are right in line with popular groups like America or Seals and Crofts. Their Canadian accents "de-countrify" the essentially country sounds. Since hippies and rednecks were not aligned at the time, the distinction was important. It's no surprise that Garcia liked their playing, nor that Clive Davis wanted to sign them. Success didn't happen, because the record industry is always a crapshoot, but it wasn't due to lack of talent.

September 7-12, 1971 Boarding House, San Francisco, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Cris Willliamson/Uncle Vinty (Tuesday-Sunday)James And The Good Brothers returned to headline another week at The Boarding House. It had to have helped to have played an hour on the biggest rock station in San Francisco. They were supported by Cris Williamson and Uncle Vinty, both of them further examples of the types of interesting acoustic acts that were struggling to find a foothold.

Cris Williamson, from Deadwood, SD, had put out three folk albums on Vanguard as a teenager in 1964-65. By 1971, she had released an album on Ampex, recorded in San Francisco and New York. She was getting the typical singer/songwriter push of the era, but getting nowhere. At this time, she was booked as "Chris" Williamson, whether by choice or not isn't clear. In 1975, having been dropped by Ampex, Williamson founded Olivia Records, a label run for women that was run by women. Olivia Records released excellent music for its own audience. For all Williamson's talent, the music industry in San Francisco (nor elsewhere) was unable to find that audience.

Uncle Vinty (Vinton Medbury, 1947-94) was essentially a performance artist who played the piano. He sang and played the piano, told jokes and did magic tricks. He often performed in a Viking hat. Originally from Rhode Island, he had come out to San Francisco around 1971. He ultimately ended up in Milwaukee, although he continued to tour around. He died early, but is fondly remembered on the internet. Uncle Vinty didn't fit into any pre-existing box, however, and San Francisco music scene didn't really know what to make of him.

September 17-20, 1971 Lion's Share, San Anselmo, CA: James and The Good Brothers/Cris Williamson/Uncle Vinty (Thursday-Monday)

The same bill went on for four days at the Lion's Share. The ads are confusing, and James And The Good Brothers may have done a night at the New Orleans House during this weekend.

September ?, 1971 The Ash Grove, Los Angeles, CA: James And The Good Brothers/Carol Hunter

At this point, the performing trail of James And The Good Brothers goes cold. We know that Columbia released their debut album in November. Various websites say that the band toured around the country in 1972. The Good Brothers website mentions memories of playing the Troubadour in West Hollywood with Mother Earth and John Hammond. It's very hard to find out historical bookings at the Troubadour--I seem to be the only person who has tried--but I can't find a trace of a date for them in 1971 or '72. That in itself doesn't mean anything, but it makes it harder to track the band. Bookings at the Troubadour were generally two acts for six days (Tuesdays through Sundays), so they probably played two different weeks with different headliners.

Per the websites, James And The Good Brothers didn't like touring around. Also, the album didn't go anywhere, and it was very hard for a band to get much traction if their record company had lost interest in them. Bruce and Brian Good wanted to return to Canada and their families, so the band broke up. Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead had heard them, recognized their talent and kick-started their careers. Since the band had met Garcia in July 1970, James And The Good Brothers had released an album, played all over the Bay Area and then the country. That was a bigger bite of the apple than most bands got. The Grateful Dead would try the model one more time with the Rowan Brothers (the subject of a future post), before Garcia and the crew decided on an entirely new and different model for building their musical empire.

|

Pretty Ain't Good Enough, the 1977 lp by the Good Brothers

|

AftermathBruce and Brian Good returned to Richmond Hill, outside of Toronto. They joined with their younger brother Larry Good, who mainly played banjo. Initially, they started gigging around in 1972 as The Good Brothers. By 1975, they had a thriving career in Canada. They put out numerous albums, many of them went gold in Canada, and they won various awards in a career that extended over 40 years. Now, Canada isn't the States, and success there is on a narrower scale. Still, the goal of almost every professional musician is to make a living making music, and not have to get a real job, and the Good Brothers did that.

As if the Good Brothers success wasn't enough, if you will recall, singer Margaret McQueen had left the Kinfolk and married Bruce Good.

Their sons Dallas and Travis Good formed The Sadies in 1994. They started recording in 1998. They, too, have had a thriving career. They have recorded numerous albums, as well as collaborating with artists like Neil Young, Neko Case and John Doe.

In mid-72, when James And The Good Brothers broke up, James Ackroyd returned to California. Initially, he was the bass player for Canadian guitarist/songwriter David Rea and his band Slewfoot. This, too, was a Grateful Dead connection, as

Bob Weir (of all people) had co-produced Rea's Slewfoot album for Columbia in 1973. Ackroyd stayed on as Rea's bassist until at least the end of 1973. By late 1974, Ackroyd was fronting the local band James And The Mercedes, which included Frankie Weir (Bob's then-wife). Ackroyd seems to have died in 1999, fondly remembered by his friends and former bandmates.